Originally from Indiana, AJ Nafziger received his BFA from the University of Indianapolis and MFA from Arizona State University. His recent work draws inspiration from a variety of sources, most notably science fiction, surrealism, and the scenic landscapes surrounding Arizona, where he lived for three years while completing his MFA.

After a recent move from Phoenix, Arizona to london, the surreal landscape drawings he is currently developing focus on his travels through the American Southwest and serve as a reflection on his memories exploring this scenery and how the personal significance of these experiences in his life has shifted from the present to the past.

Nafziger’s artwork has been exhibited widely across the United States and recently in the UK and featured in publications such as Direct Art, Artist Portfolio Magazine, Studio Visit, and Artmaze.

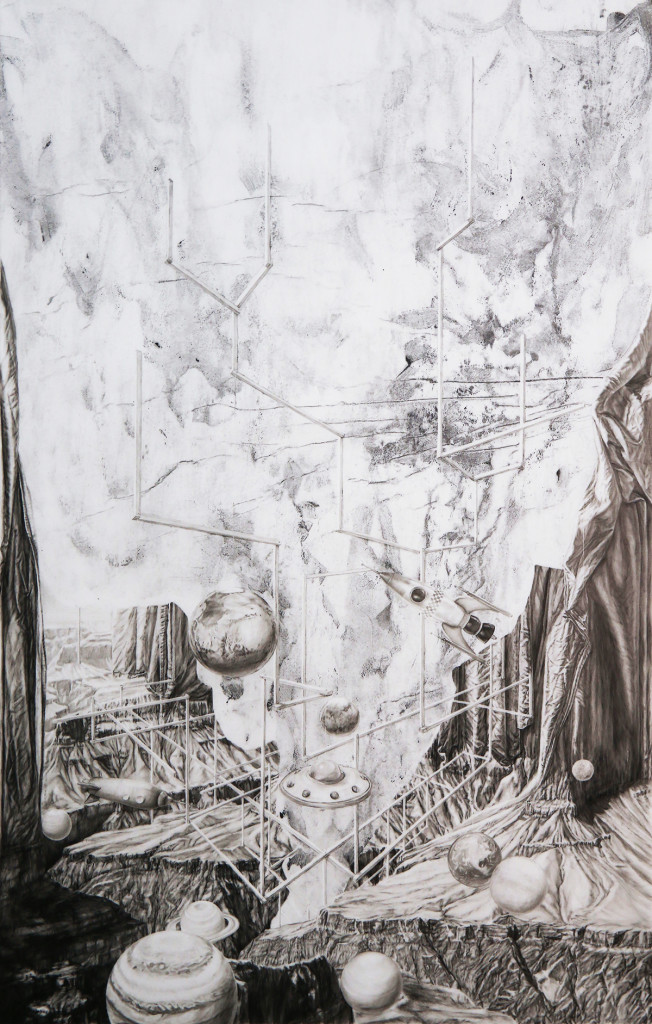

Pencil and liquid graphite monotype on Yupo paper. 87,6 x 55,8 cm – 34,5 x 22 in

2015

Guy Marshall Brown: Where did your interest in art production originate?

AJ Nafziger: With a father who was an art teacher, I became interested in drawing very early. While almost all kids like to draw for fun, I remember taking it very seriously even at a young age. I loved using drawing as a way to depict scenes from my imagination, so I have always valued realistic detail and clear depiction. It was not until college that I began to paint in oils and I have actually only recently branched out into experimental and mixed mediums. Although the materials I choose to use have transformed drastically over the years, the concept is still the same: to create and depict scenes that I hope convey the types of ideas that I enjoy thinking about or struggle to understand.

G.M.B.: Your work has a very distinct signature to it. How has this signature developed over time?

A.N.: The most consistent thing I have always tried to do is to just keep challenging myself, picking imagery that I feel is difficult to draw or paint, continue bringing new elements into my scheme of work, and depicting them as accurately as possible. In college, I made my first serious attempts at the challenge of depicting people accurately through drawing and painting the figure. As fabric is often included in figure studies, this led into a kind of obsession with fabric and folds, which I found could be almost endlessly complicated and fascinating to understand and render. You can see this in nearly everything I have done in the past five or six years, so I guess fabric forms would probably be the most definitive characteristic of my art. If you see my work from around 2011 to 2013, it is mostly made up of mysterious floating forms of fabric in front of blank backgrounds, with a few other elements in different pieces. In the past few years since then, I have been focusing on bringing these same types of ominous forms into more complete environments with real depth and space that truly feel like windows into another world or reality rather than just an empty space or a void.

The drawings I am currently working on blend the folds and wrinkles of fabric into the endlessly intricate natural elements of landscapes, transforming one into the other. Dense foliage and rock formations gradually become wrinkled fabric, floating up into the air. The details of these two elements actually resemble one another in many ways, especially when colour is removed. The drawings are kind of surreal landscapes that mix natural formations we think of as permanent with the unpredictable movement of fabric forms, showing how easily the world around us can change.

G.M.B.: Often your work seems to portray futuristic landscapes. Do you consider these to be utopian or dystopian environments?

A.N.: In the series of three drawings titled The Future Is Not What It Used To Be, I mostly want to show landscapes that are shifting from the present into the future or into a currently unrecognizable state. The drawings in this series depict the runaway growth of mysterious, abstract forms within a reality that shift between ideally planned fictional futures, the illusion of logical governing patterns, and the detailed, actual landscape of real life. I don’t really think of them in terms of dystopian or utopian. Thinking of the future in this way means attempting to predict it, taking elements of our present state and projecting them along a linear path. I try to avoid this type of prediction and instead attempt to represent the errors of prediction itself. I read a lot of science fiction and am, more than anything, just entertained by how these visionary authors of the past viewed the future we are currently experiencing and how it rarely progresses along such foreseeable routes. In a similar series of eight smaller drawings titled First Variety, Second Variety, Third Variety, etc., I imagined similar forms being grown in zoo-like enclosures decorated with childish outer space and futuristic illustrations and patterns. These were meant to show the error in trying to plan for an unpredictable future based on our own naive imaginings of what that future would hold. The forms eventually grow beyond our predictions as the surrounding environment decays and becomes dated, while the future moves forward on its own.

G.M.B.: Your painting Golden Path is built up through the use of numerous small panels. Could you please explain to us your choice to do this?

A.N.: The grid of panels is referencing an old computer game called Pipe Dream. The point of the game was to piece together a series of pipe sections to contain the flow of some kind of ooze. The ooze would continuously flow through the sections of pipe as you placed them and if you couldn’t keep up, it would spill out and you would lose. You could lay the pipe down in straight or curved sections, similar to the golden pipe-like form in the painting. The idea of trying to keep up with the growth of a substance that is expanding beyond control is the same concept I was trying to represent in my recent science fiction series of work, so I thought referencing the aesthetic found in this game would be an interesting way to tie in something recognizable to hopefully hint at this theme.

G.M.B.: Surrealism seems to be the most prevalent theme within both your paintings and your drawings. Please discuss the relationship that you have with this theme.

A.N.: Surrealism is definitely a movement I have learned a lot from. Because of the way the surrealists developed their imagery using processes of unconscious thought, there is never any obvious theme or message being conveyed in their work, which I think gives surrealism an endless appeal and allows viewers to project their own thoughts. I think imagery meant to convey a concrete concept often becomes boring once the concept is understood. But above all, I admire these artists for being able to create work with such a rich philosophy, based on principles of psychology and the unconscious, while at the same time not being afraid to appear absurd. I feel like they created deeply serious artwork yet somehow managed to not take themselves too seriously, which I think is a problem many artists have. Rene Magritte is my favourite surrealist artist and I think his work is probably the best example of what I love about surrealism. His art is so playful and full of humour, but in the end I think it challenges us to question aspects of our lives and realities that we take for granted as ordinary, familiar, or predictable.

G.M.B.: Visually your paintings are reminiscent of the Vanitas movement. Is this something that is heavily considered?

A.N.: I really do like symbolic still life paintings and the Vanitas movement, but I actually had not considered it as a direct influence before. I always find it interesting how objects take on different meanings when paired with other objects, which is something I have explored in the past. A while ago I did a series of charcoal and carbon pencil drawings based on ink blot images, like those used in Rorschach tests. I would just look at the images, record my perceptions, and then try to realistically draw the results. I did twelve of these drawings and the imagery varied widely from piece to piece, but there were some similar objects found throughout. There were a lot of skulls and flowers. I’m not sure what that says about me as a subject in a Rorschach test, but it definitely is reminiscent of the Vanitas movement, so perhaps it is a subconscious influence.

G.M.B.: What other artistic movements and which significant artists have inspired the development of your artistic practice?

A.N.: Surrealism is definitely number one, but I have also always been tremendously inspired by MC Escher, whose work, for me, stands on its own. I really love looking at a picture and wondering, “how is that possible?” Obviously, a drawing or painting isn’t real, so the answer should be easy enough. But there is believability about great artwork, like the work of MC Escher, that makes you accept them as real while you are viewing them, like watching a movie or reading a novel. Rarely when you are immersed in a movie would you constantly remind yourself that it’s fake, at least not without ruining the experience.

I think this has become more and more difficult to accomplish with painting and drawing now that other art forms actually capture reality more easily and effectively, so when an artist does it, I am truly amazed. As the environments in my work have become more realistic, I have really worked to employ linear perspective, as Escher often did, to establish and accentuate depth to draw the viewer in and hopefully help immerse them in this fictional world. So I have been revisiting Escher a lot and am still as completely blown away as I was when I was a kid.

G.M.B.: Your Self-Portrait in oil is an interesting contemporary take on a Renaissance portrait. Tell us more about this painting.

A.N.: This painting was meant to show me as an artist experiencing inspiration in the form of unconscious or undefined thoughts and ideas. The light bulb is a symbol used in cartoons to express the spark of an idea. The light comes on over the character’s head when a new concept or thought has just dawned on them. For me, in the initial stages of planning a picture, I rarely know for sure what the imagery is exactly going to be and usually have no clue about its meaning to me. These are things I discover and refine as I work. But in this portrait, I tried to create a twist on the classic cartoon light bulb symbol by showing thought as a scattered mess of different elements, some of which are dissolving into space.

G.M.B.: Your education was quite strongly rooted in painting and drawing. Have you ever experimented with other media and how do you feel about painting and drawing in the expanded field?

A.N.: Drawing has always been my favourite since I was a kid, although when I studied art at college I began painting and was educated in both. For quite a while, I just stuck strictly to painting in oils and drawing in charcoal or graphite. I wanted my pictures to act as windows to fictional worlds, so they needed to be unified and seamless. I think this is difficult to do with mixed media approaches as it is hard to be immersed in a picture when you can clearly see the seams in the materials used to create it. So for a long time I always had a tendency to steer away from mixed media altogether. This has changed somewhat in the past few years after I took a mono-printing course while earning my MFA. I draw and paint in a very controlled way, so it was liberating to play with the element of chance that mono-printing introduces. I experimented with some different techniques and tried to introduce spontaneity through mono-printing into my drawings and paintings. This is actually what ended up resulting in this whole science fiction themed body of work. I was thinking about how the element of chance makes the future unpredictable. Relating this to futuristic fiction, I ended up doing this series of work showing what happens when we attempt to enforce control on something uncontrollable. I have continued to experiment with mixed media and recently have tried to figure out a new approach to purposefully acknowledge the seams between mediums within a picture as a way to depict the split between two different, competing senses of reality. I’m not sure what will come of it, but I’m having fun right now at least.

G.M.B.: What does the future have in store for you?

A.N.: Like my recent science fiction themed work, the pieces I am currently working on reflect the relationship of the present and future, but in a much more personal way. last year, I moved from Phoenix, Arizona to london, England and have been working on landscape drawings focusing on my travels through the American Southwest, reflecting on the pictures and memories I have of this scenery and how these important experiences have shifted from present to past. I think that when I am ready to be done with this series of work, I will get back into painting. Recently, I haven’t had the space to pursue many of the ideas I am having for large paintings, but when I do, I plan on revisiting some other previously unexplored themes from science fiction that I find fascinating.