Farniyaz Zaker is an Iranian born UK-based artist. Located between architectural theory and gender studies her art-practice and writing largely deal with the nexus of body, society and place. Her practice ranges from site-specific installations to video, sound and drawing. Much of her practice explores how bodily practices and spatial awareness define our sense of identity, belonging and the very concept of knowledge. Her work is both generative and corrosive of boundaries, such as the one between architecture and clothing. It often employs transparency and opacity, repetition and memorisation, text and textiles and plays with notions of the public and the private, the physical and the psychological. She has been the recipient of numerous grants and awards.

In 2011 she was awarded the Lamb and Flag scholarship from St John’s College of the University of Oxford, which enabled her to pursue a Doctor of Philosophy in Fine Art. She was awarded the Birgit Skiold Memorial Trust Prize in 2011 at the International Print Biennial; and most recently, she has been selected for the Arte Laguna Prize 2014 (Sculpture and Installation Section), in Venice, Italy.

Francesca Pirillo: How did you get into art? Did you attend art school?

Farniyaz Zaker: I have a long-standing interest in Fine art, particularly in textiles and the way they communicate with architectural space. My work has been exhibited internationally since 2002, garnering numerous awards. In 2006 I graduated with a Ba in Textiles and Carpet art Studies from the art university of Tehran, where I have studied the techniques, artistic traditions and cultural/geographical particularities of textiles and carpets. But it was only in 2008, when I embarked on an ma in Textile Design at the Winchester School of art (Southampton university), that textiles and carpets became an intrinsic part of my practice. During that period, I was particularly interested in the richness of garden design carpets and textiles, and in their mutual relationship with architecture. Subsequently, I decided to engage with this subject not only through my art practice, but also theoretically and academically. I had the privilege to be awarded the Lamb and Flag scholarship of St John’s College in 2011, which allowed me to pursue a Dphil (phD) in Fine arts (theory and practice) at Oxford university’s ruskin School of art. Completing my studies in 2015/16, I used this time to study how sexuality has been embodied architecturally, and to express my insights and questions through my artworks.

F.P.: What are your artistic influences?

F.Z.: The spaces and the places that I used to dwell on have had a direct impact on my practice. I believe that the built environment surrounding us is invested with meaning and engenders human subjectivity. And, while I try to express this through my work, the latter is itself shaped by these processes. There are also a number of artists that have influenced my work, among whom I should mention Eva Hesse, Rebecca Horn and Mira Schendel.

F.P.: One of the features of your work is the use of words, like in [text]tiles, [in/out]side…Could you explain to us a bit more what role words play in your conceptual process?

F.Z.: Words and text are an integral part of my art practice. I enjoy playing with the parallels between text and textiles, and I’m trying to create a language of textiles. My engagement with language and text as a medium began with a series of artworks that used, altered and recreated textiles, especially carpets. These works compared the intricate patterns and forms of certain textiles to text. The design of carpets, for instance, has often been a vehicle for the stories of those who have woven or commissioned them. moreover, there are numerous structural similarities between text and textiles, such as their linear and accumulative nature. In my practice, words – rather than being mere passive signifiers – are involved in the making of meaning and the evocation of various associations and experiences. I use words to establish connections between different kinds of materials and spaces.

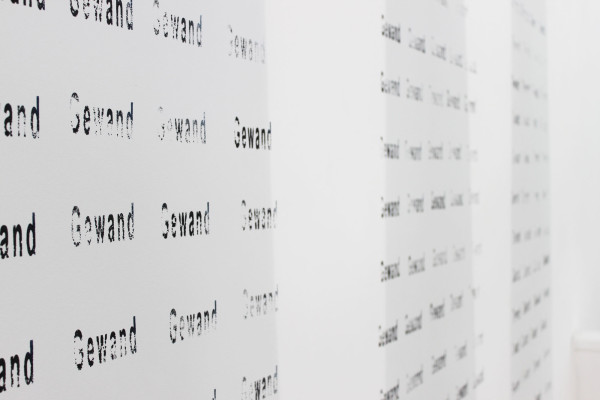

F.P.: Can you talk about [Ge]wand series; How did it evolve?

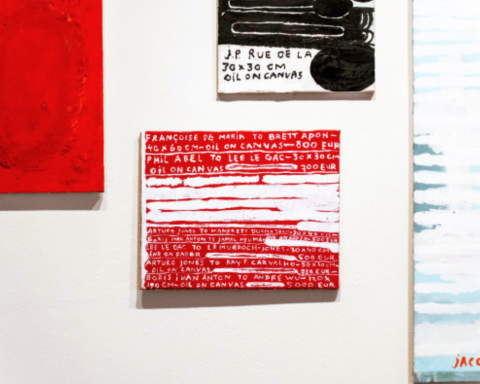

F.Z.: This series stemmed from my doctoral research, more precisely, from my discovery that the German words for wall (‘Wand’) and dress (‘Gewand’) share the same root. I decided to exploit this for my practice. all the three works – [Ge]wand I (2012), [Ge]wand II (2013), and A black dress, a red dress ([Ge]wand III) (2013) – invite the audience to read these words through different materials and contemplate the relation between gender, language, textiles, text and architecture.

F.P.: What subjects do you deal with in your art?

F.Z.: In my practice, I position the body, architecture and clothing in a reciprocal relationship. My works dwell mostly on the interactions between and within different built environments. My practice, for instance, asks why open space is a symbol of freedom, threat and vulnerability (the etymological root of the word “bad” is “open”), while place, in contrast, is an enclosed space that symbolises and suggests safety. My sculptures and installations tend to reference the body, clothing, architecture and language. They are often site-specific, i.e. installed with sensitivity to their environment and context. I aim to place my work in a way that allows it to interact with the built environment surrounding it. My work tries to use and redefine the space in which it is installed; and it highlights that the build environment is not a static and neutral space, but that it is empowered by (and empowering) human subjects.

F.P.: What about Primeval Relationship project? Can you talk about this series and the idea behind it?

F.Z.: Since 19th century, architects and theorists of architecture have paid increasing attention to the links between textiles, clothing and architecture.

Primeval Relationship I and II investigate these connections. Primeval Relationship I covers the walls and floor of the gallery with four hand-woven carpets and their elongated fringes. The four carpets are devoid of ornaments, akin to the walls of a modern building. Primeval Relationship II is a cloth pillar that stands in the middle of the gallery’s space, rhyming with the space’s structural columns. Both works allude to Gottfried Semper’s (1803-1879) theory regarding the origins of architecture in textiles.

F.P.: What role should the artist play in society?

F.Z.: In my opinion, one’s practice should be informed by, but not limited to, one’s own personal story and experiences. In other words, the artist should be able to reflect on her/his ‘contemporaneity’.

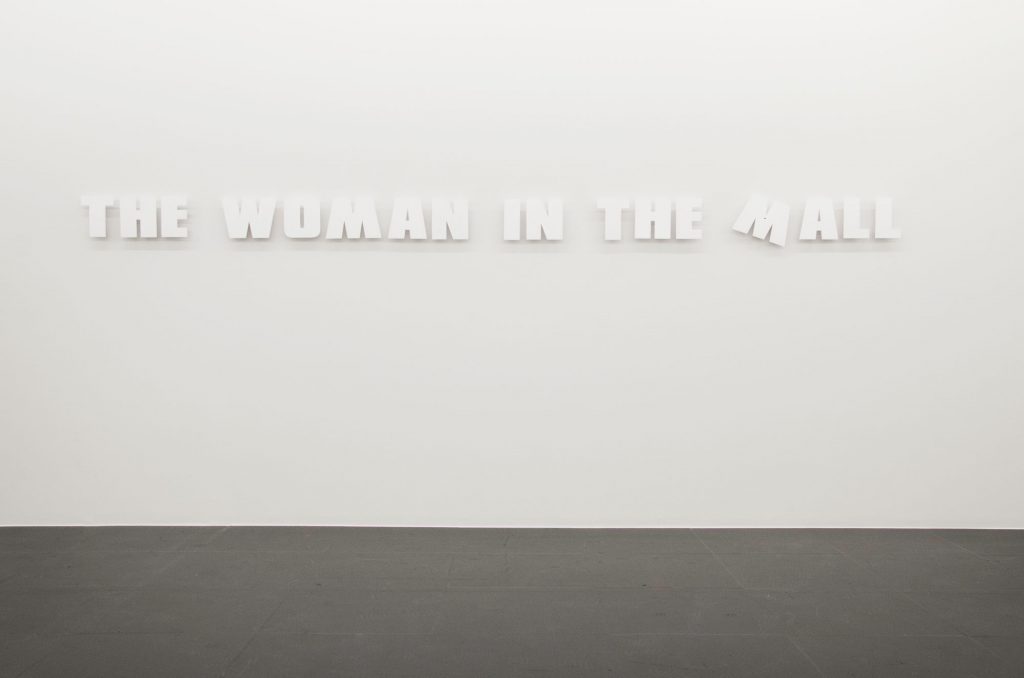

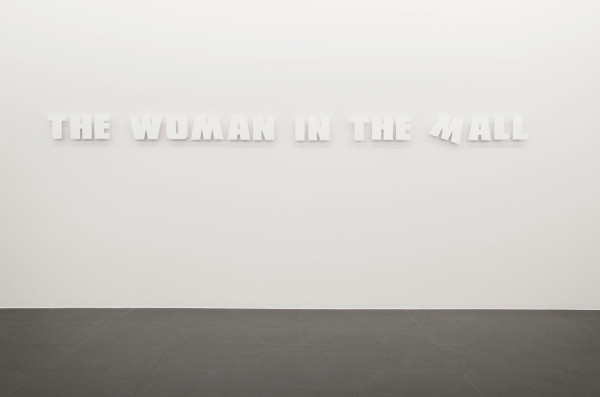

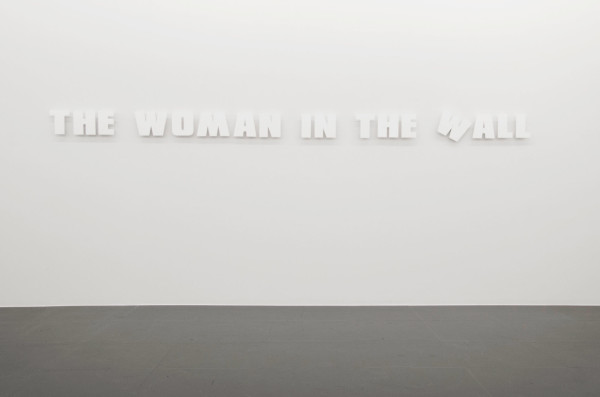

The Woman in the W/Mall

Something There Was That Must Have Loved a Wall, Pi Artworks Gallery, Istanbul, 2016 Electric motor and wooden letters 2016

The Woman in the W/Mall

Something There Was That Must Have Loved a Wall, Pi Artworks Gallery, Istanbul, 2016 Electric motor and wooden letters 2016

The Woman in the W/Mall

Something There Was That Must Have Loved a Wall, Pi Artworks Gallery, Istanbul, 2016 Electric motor and wooden letters 2016

F.P.: Could you describe to us the Untitled-2010/2011 site specifically? How did you come to the project?

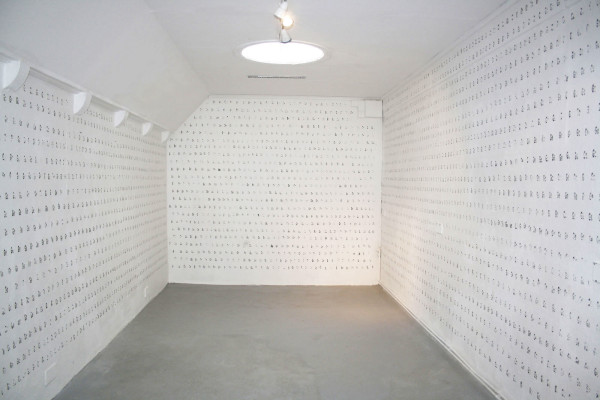

F.Z.: Recent years have witnessed a growing interest in middle eastern art on the art market. It seems that some artists have promoted themselves (or were promoted) by reproducing exotic and Orientalist clichés about Islam and muslim women. The image of a veiled woman in black (often connected to violence and oppression) has been one of the hallmarks of this phenomenon. Untitled-2010/2011, which was exhibited at the Sharjah art museum and consists of a wallpaper featuring a repetitive colourful veiled woman motif, both symbolises and challenges (through inversion) the mass production of such clichés.

F.P.: What role does autobiography play in your work?

F.Z.: The spaces and places that I have dwelled on have engendered a personal significance that exceeds their physical dimension and is reflected in my practice. In other words, my works are an account of my spatial existence.

F.P.: What are you working on at the moment?

F.Z.: I am working on an installation entitled Poetics of a Non-Place. The term non-place was coined by Marc Augé, who used it to describe places that are incapable of evoking a real sense of dwelling, such as stadia, airports, terminals and refugee camps. I have already mentioned that some of my work engages with the dichotomy of open space = danger vs. enclosed space = safety. Poetics of a Non-Place breaks down this dichotomy, by creating an enclosed maze – like space that is also open and transient and hence incapable of evoking a sense of dwelling and belonging – a non-place. The work is an examination of the spatial dimensions of liminality, ranging from boundaries, borders and disputed territories to environments that people pass through but do not live in.