Archiving Encounters is a new series dedicated to the exploration of archives in contemporary art practices. These explorations do not follow a specific set of parameters but start from a general understanding that archives are groups of objects, traces of actions, that can take different forms: including, but not limited to, photographs, drawings, diaries, letters, sketchbooks and official documents. Archives are often seen as hidden away, impenetrable and suspended in time, waiting to be re-activated by users. Archives are the product of the social processes and systems of their time, presenting the stories of those included within those systems and reproducing the absence of those excluded. So, rather than proposing a fixed definition of archives, and the kind of work that can be associated with them, Archiving Encounters takes conversations with artists, and their practices, as starting points to encounter the different kinds of archives they choose to work with. Often artists use ‘the archive’ as a theme itself, produce new taxonomies, respond to real archival materials to critically challenge modes of knowledge production, or use it as a framing device to invent characters or events from the past that are put in dialogue with the present to shed new light on contemporaneity. In this sense, this series has two purposes: documenting encounters with archives and exploring their possibilities, and archiving the encounters with the artists, who through a deeper understanding of their work, allow us to see the meanings of archives and archival practices.

The idea of the archive is similar to that of the collection, and that is also one of the reasons why contemporary institutions are ever more eager to engage with them, in the sense that they both constitute a group of objects that is actively gathered and preserved. Both archives and collections constitute fertile terrains to ask questions of power, how we organise and build knowledge, what we choose to preserve for the future. Similarly, both for archives and collections we may know the context which produced the objects, however as a set of objects they, in theory, present a slight difference. Collections can be created with the sole motivation of collecting, the gathering of different objects where material connections can be pre-established by the interpretative work of collectors and curators; archives, instead, frame the items in a context or theme, so they become a set of records that can shed a light on each other, where the job of the archivist should be that to be as objective as possible in their preservation. Archives, in this sense, invite interpretations from users to re-elaborate on the materials and make their present and future meanings never fixed. It is by embracing this discursive approach, what Sue Breakell calls ‘negotiating the archive’, that Archiving Encounters propose to delve into the exploration of archives as a domain for creative exchange through the practice of contemporary artistic practices.

Alice Pedroletti

DIN DIN , 2019

Archive images (print on A4 tracing paper)

MAC – Museo di Arte Contemporanea Lissone (IT)

Courtesy of the artist and ATRII

Living the Archive: Alice Pedroletti

Alice Pedroletti (Italy, 1978) lives and works in Berlin and Milan. As an artist-researcher, she investigates the meaning of archiving as an art practice focusing on identity and memory. Her work moves between various fields (science, literature, history), but she is mainly interested in geography and architecture. She questions the image’s significance through a physical relationship between photography and sculpture concerning temporality, fragility, and matrix in both disciplines. She won the Italian Council 9th Edition (2020), a program to promote Italian contemporary art in the world by the Directorate-General for Contemporary-Creativity of the Italian Ministry of Culture.

As an artist-curator, she founded ATRII and its Open Archive for the future, a collective and nomadic project hosted at Cittadella degli Archivi, Milan Municipality Archive. She is a fellow at Rabbit Island Foundation and TSOEG – Temporal School of Experimental Geography: artist networks focusing on ethical and experimental art practices concerning the environment and she’s a member of AWI – Art Workers Italia. Her work and ATRII have been presented in several Italian and international galleries and institutions, along with talks and residencies. Among these: BOZAR – Center for Fine Art (Bruxelles – B, 2021), ZK/U – Center for Art and Urbanistic (Berlin – D, 2021), Unidee – Fondazione Pistoletto (Biella – IT, 2020), Royal Geographic Society (London – the UK, 2019), Museo del ‘900 (Milan – IT, 2017).

This text has been inspired by several conversations with artist Alice Pedroletti, which opened a dialogue on how we think about what archives are, how they are generated, how they can be used and, in particular, how these questions are reflected in the work of contemporary artists. Coincidentally, the first conversation happened while on a guided walk to explore the history of a neighbourhood in Venice. The city then offered itself as a prompt to think of it as an open-air archive. Instead, the publication of this article coincides with the final phase of the artist residency at the ZK/U Center for Art and Urbanistics in Berlin. I take it as an opportunity to reflect through her experience and artistic practice on urgent questions on how the pandemic has impacted life and shaped the work of artists. While Pedroletti’s latest works give us a snapshot of the contemporary time, in her previous works we can also see how they signal to the ongoing research that constitutes the artist’s practice, which brings to the fore, with renovated importance, questions about the meaning of artistic labour in engaging with how we construct culture and society, and everything that derives from them, through the accumulation of knowledge and objects, how we preserve them for the future, how we create new knowledge and new things and eventually how we engage with the past, the present and the future.

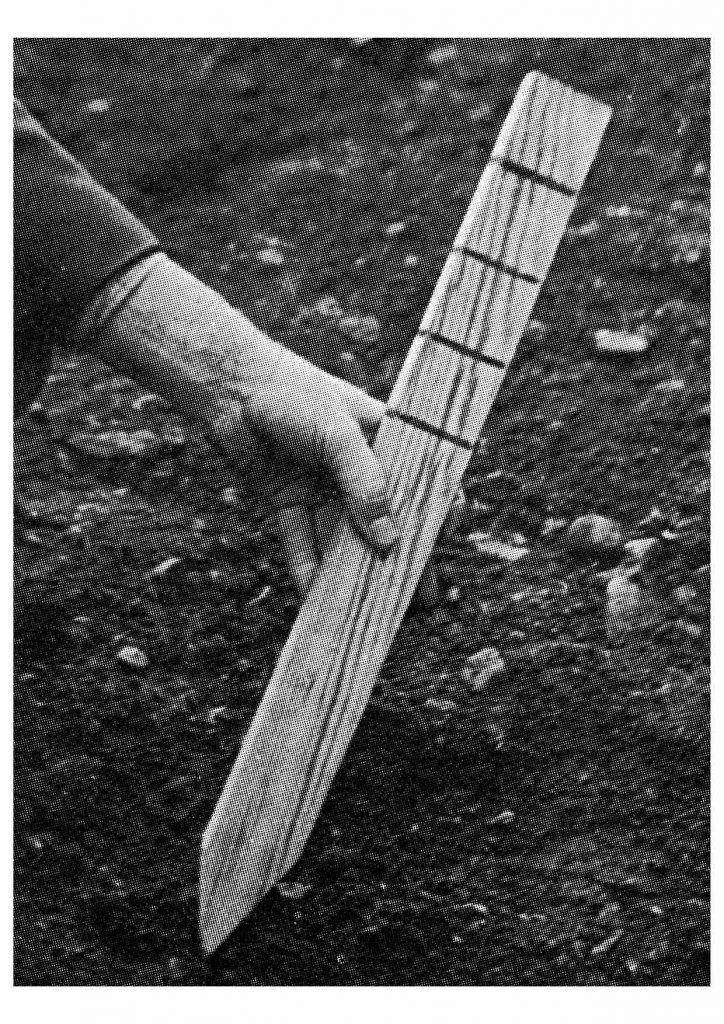

Pedroletti’s practice is not bound to a medium but spans from photography to sculpture, from drawing to installation and others to play subtly with objects, images and symbols to destabilise viewers’ assumptions and preconceptions. For example, in DIN DIN (2019), she used text, sculptures and several images from an old handbook. The images show an unknown person engaging with some sort of building work: they have a similar aesthetic and gestuality of the photographs that can be usually seen at retrospective exhibitions of renowned Arte Povera or land artists from the ‘60-‘70s. By extrapolating and decontextualizing the images, she created a fictional character, as if they were archival images documenting the work of an unknown artist or designer, lost in the time frame of the art system. DIN DIN reflects on notions of standardisation and challenges visual stereotypes, questioning the symbols and signs of what we understand as art or daily life. If we can misinterpret these images as if they were the real documentation of an artist at work, does that mean that we have developed a standardized notion of what an artist’s work looks like? Alice reflects on who decides the standards and how the media themselves shape how to see and consume art today.

Alice Pedroletti

DIN DIN , 2019

Octometric brick made with kinetic sand

MAC – Museo di Arte Contemporanea Lissone (IT)

Courtesy of the artist and ATRII

ATRII

Archivio Aperto (Open Archive), 2015

ATRII Archivio Aperto – Project folders

Cittadella degli Archivi, Milan (IT)

Courtesy ATRII

These questions are layered throughout the work, in the subject of the photographs, in the medium, in the context and in the final artwork at the MAC – Lissone Museum of Contemporary Art. She uses the archive as a methodology to organise her own work, as well as the starting point for the research from which she, in the end, produces a totally new artwork imbued with the meaning of the overall work. Through the installation, conceived as a fictional minimal exhibition, one can finally understand the ‘plot’ of both artists: the unknown person is not an artist but more likely a gardener, as the images came from a manual that provided standard tools and tips to create what would be ‘the perfect garden’. The photographs were displayed as A4, the most common standard size for printing. The final, new object, created out of this process, was a simple, recognisable optometric brick made of kinetic sand which, while it is usually used as a standard measurement, here never finds a fixed form. In this work, we can already see a recurring methodology: the artist’s work happens through archival research, subtraction and the creation of an ever-changing object. In the end, the artist herself disappears in favour of the fictional artist, who she created from archival materials that could be coming from the museum, but that were actually found in a second-hand bookshop. In this way, her work re-activates the idea of the archive by creating a new one and keeping it in constant motion, inviting us to question the apparent truth that can be extracted from books and destabilising its own nature as a fixed, permanent collection of objects.

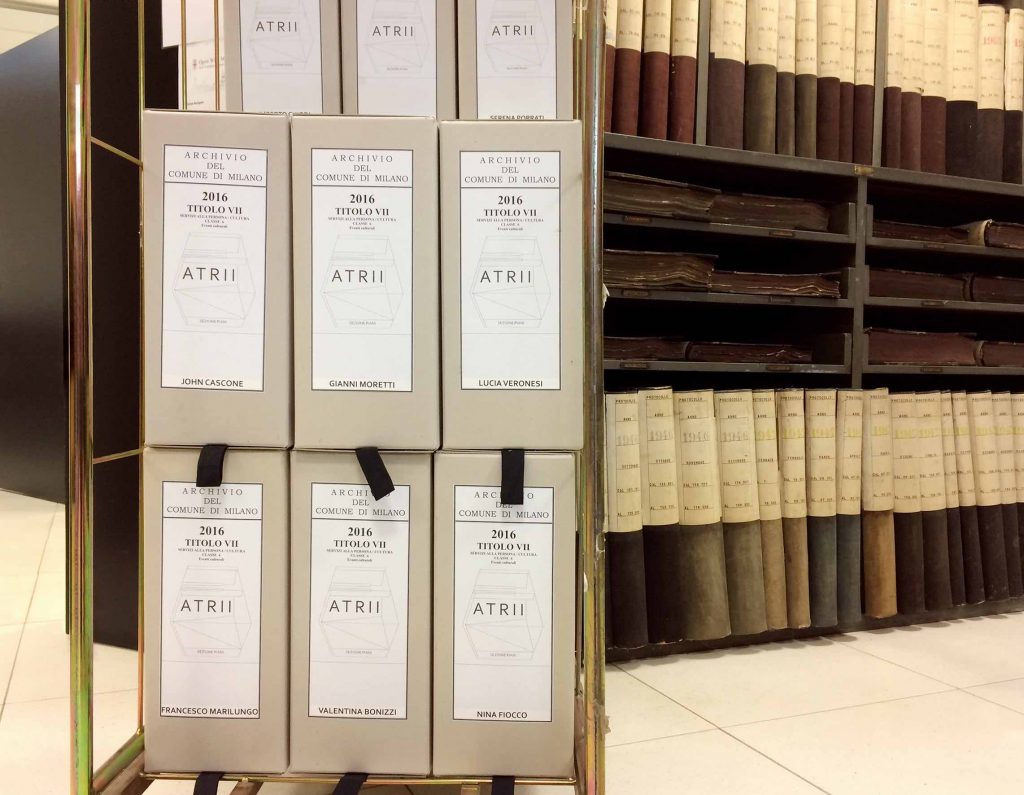

This approach is also explored through the collective ATRII, which she found in 2015 in Milan. ATRII brings together artists to work with the liminal quality of atriums: lobbies and courts at the entrance of buildings that are at the same time private and public as they formally belong to each one of the people living in the building, but they also stand in between the public space of the street. All invited artists are required to identify in an atrium or in the concept of ‘atrium’, a link with their research and work as the basis for an artwork – or a project of an artwork – that could highlight the links between art, territory and inhabitants. The outcomes of the research are archived at Cittadella degli Archivi, the Municipal Archive of Milan, and they are also published online. In this sense, ATRII is an open and living archive, continuously expanding until the realisation of the idea into the physical space of an atrium.

This methodology can be compared to what is known as the archive continuum. Developed as theory (the ‘record continuum model’) first by Australian approaches to archival sciences, the archive continuum sees archiving as a process in constant ontological unfolding. This understanding expands the life cycle of records beyond the initial creation and the final filing away, after they exhausted their purpose, to that of objects linked to their context of creation, from which they were ultimately disembedded in the process of conservation, and that can be represented and used in new circumstances, renewing the possibilities for their value. This change of perspective turns archives from ‘excavation sites’ into ‘construction sites’, as Hal Foster wrote in his article An Archival Impulse.

Alice Pedroletti

Islands never cry, 2021

Site specific installation (three sails 4,5×1, sailing ropes, wind)

ZK/U Open House, Berlin

Courtesy of the artist

Alice Pedroletti

Islands never cry, 2021

Drawings on paper

Site specific installation (three sails 4,5×1, sailing ropes, wind) – View from the artist studio at ZK/U

ZK/U (Studio 12) Open House, Berlino (DE)

Courtesy of the artist

The application of the idea of the ‘archive continuum’ can be seen in the work (cose)rose (2018) in collaboration with artist Lucia Veronesi, also part of ATRII Collective. Alice collects archives, which bring together slides affected by what is called ‘magenta shift’: a temporal process in which the cyan and yellow colours of the slides disappear, leaving only magenta as the prevailing one. A small part of her collection was used in (cose)rose, meaning ‘pink things’, to investigate the idea of fragmentation, metamorphosis and mimesis between art and architecture, literature and photography. The artwork functions again by subtraction: neither the historical artefacts nor their photographs were taken by the artist, who acknowledges partial authorship given the inherent element of collaboration that exists when using archival materials, and it highlights the defecting nature of the objects, which slowly decay, losing something of themselves. The diapositives used once as a teaching tool in school, here appear under a, literally, new light while maintaining recognizability as icons fixed in our memory. By projecting the images in an atrium, the two artists want to reinforce the transient nature of the object in a space that is also a passageway. In front of the projection, a mirrorball reflects a portion of the image all over the space, creating an immersive, kaleidoscope-like, ambience that forces the viewers to consider the myriad of future narratives and ways of seeing that these materials could take on. The process of subtraction from a fixed state, with the purpose of reinvention, is made even clearer by the striking contrast that results from the black hole that the mirrorball creates by blocking out a portion of the projected images.

However, Pedroletti engages with archives in a broad sense, conceiving spaces and people as living archives too. In Study on a floating island (2018), she adopted a cartographic approach to producing a map that could include sensitive elements, shreds of evidence of the past, memories, recent lived situations, changes in the landscape, traces of the permanence of living beings on the island. Alongside archival materials collected over the years by the artist, which were used here to expand on how we think of ‘islands’, she created a site-specific wall/archive following the shape of Isola Comacina, where she was on a residency. The title of the project Study on a floating island suggests that we consider the island as an object that exists outside of the water, what we normally see, as well as existing below the water. The map explored the boundaries and contours of the island searching for an imagined access point to the world beneath the surface. The whole project took an inside-out/upside-down approach working with temporality and space: the outside world was brought inside the architecture, and the map showed possible entry points to the bottom of the island and it was accompanied by drawings that showed its possible underwater conformation. From pieces of lightweight concrete, she made several sculptures recreating the shapes of the island in its complete form so that it could be seen in its entirety. The interlayer of the media in this work, where each step is used to investigate the process itself, questions to what point something exists in itself and how we can engage with it. Interestingly, while the map shows the life of the island as unfolding through time and seeks to show entry points for what cannot be seen, what is absent from sight, the sculptures also never reach immanence as they are carved, photographed and recarved, becoming the remains of the sculpture that was. Again, a work of subtraction. The artwork exists in its absence, its memory exists as fixed in the image, which works as an archive of itself: it provides a snapshot of something that is gone while it continues to exist in the present.

The themes of the archive, the atrium and the island are found again in her residency at ZK/U in Berlin, presented during the first Open House event after a year of restrictions due to the pandemic. The residency addressed the contemporary contradiction of creating collectivity in the distance while dealing with imminent questions surrounding the reconstruction and future of cultural spaces. ZK/U, invited to the 15th edition of Documenta for their community-based collective work, hosts individual artists, practitioners, urban researchers and collaborative groups, in self-contained units with living and working areas in a former railway depot surrounded by a public city park in the Moabit district. Pedroletti presented the project “The city, the island”, also a collaborative project with ATRII, which stems from a similar consideration about liminal spaces: the invisible border between the residency and the city, the juxtaposition between the private and public space, recreate the conditions of an atrium that artists need to navigate through. This research is presented through a self-published zine, which will be included in the ZK/U archive, but it is also conceptualised to perform various tasks. The choice of the zine, an alternative version of a book, is loaded with various meanings: it is an archive itself of the process and research of the artist, as a book it carries knowledge and, as a guide, it becomes a means to navigate the neighbourhood.

It is important to keep in mind, to understand the experience of the residency, the spatial features of ZK/U when considering that her 9-months residency started in January 2021, concurrent with a steep increase in the number of coronavirus cases that brought a second global wave of the pandemic. While the Moabit district has historically been seen as an island next to the city centre, as it is surrounded by waterways, ZK/U – due to its characteristics – could also be imagined as an island on the island or a utopian atrium of the city. During the pandemic, the artist felt that the institution adopted even more insular qualities with its enclosed community of artists. Ideally-protected but also excluded from the water itself, during the lockdown the community of artists in residence was legally considered a household, giving them the possibility of socialisation, forbidden for the majority of the population, but also putting them in a fragile position. Could this have been a similar experience, maybe an experiment, to test how artists would survive if they were stranded on an island? What would they do with the limited resources available? Alice began to reconsider her relationship with this newly found home, the domestic and working spaces of the residency, as well as the limitations and the conditions for spatial and social interactions during the pandemic.

Alice Pedroletti in collaboration with Isaac Schaal

Archives.berlin, on going Database

Research material about islands, boats and navigation

Web version screenshot (archive images, photographs, texts, maps, QR code)

Presented in the occasion of ZK/U Open House, Berlin (DE)

Courtesy of the artist

The territorial and political conditions pushed her to imagine projects for specific emotional needs that go beyond the classical architectural space of the atrium. Islands never cry (2021) is a site-specific installation made of three sails that inflate with the wind recreating the sound of a sailing boat and, simultaneously acting as a barrier and an invitation to go beyond those barriers, perhaps using them to overcome our limitations. The installation sits on the edge between the ZK/U and the park, similar to the curtains that are sometimes used to separate spaces, like those found in southern Europe to divide the domestic spaces of private homes and businesses from the public footpath. In this sense, the sails recreate the space of the atrium; however, they are also permeated by the desire of the artist to be able to leave the residency and explore the city.

In the studio, the artist presented the ongoing archive of the process of the research during the residency. It shows a collection of images of the neighbourhood, islands and boats that have inspired her to map the space and re-imagine it. The juxtaposition of the images further reflects on the local context and the role of the artist in that context. Moabit, as a neighbourhood, can be understood through this lens if we observe the local, more permanent communities, and the temporary communities that would need to cross the water to leave and come back to the place. What does it mean to meaningfully respond to it? What is the role of the artist? Reflecting on the ambiguity of the artistic work often othered, she thinks of artists as islands for their idiosyncrasies. So while artists may be like islands in society, they are also the ones creating the ‘boats’ that help us to transcend borders, connect ideas, and arrive at new lands.

To overcome access restrictions to the building and make the archive available, Pedroletti collaborated with artist Isaac Schaal to create archives.berlin (https://www.archives.berlin/): an ever-growing online space collecting images related to the themes of islands, boats and navigation, accessible online and also on-site through a QR Code near the sails installation. It also functions as a database of images of boats that are elaborated through artificial intelligence to design a real folding boat. The idea of the folding boat has been inspired by German architect and inventor Alfred Heurich who first designed a foldable kayak in 1905 and here it is taken as the ultimate symbol for mobility. The archive, located in the Cloud, is able to bring closer artists, publics, ideas and images that would be otherwise, in reality, far from each other. The limits of authorship and agency are often tested in Alice’s practice, even for the project “The city, the island” she collaborated remotely with different artists around the world. In these relationships the roles interchange making sometimes the artist just a marginal actor, almost becoming herself the audience of her work, on which, though, she still maintains some form of authorship.

Similar to islands that self-reproduce and manage, Schaal and Pedroletti are training the AI through an autopoietic process where the digital archive then becomes alive. Once again, the artist has to relinquish some of her power over the work. Likewise, an analogic archive, which needs the reactivation from its users, the project of the folding boat could only be actualised when the artist, or someone else, would be able to access the design created by the machine. In this last work, we can see how Pedroletti treats archives not as dead repositories but rather as a living, fertile ground on which we can build new ideas. In a previous text she wrote about archives, she says:

“‘Living” typically means “life”: with its flow, its endurance, its survival. It generally refers to the natural being destined for a predefined cycle. It also reminds me how necessary it is to rethink the Archive itself: like a body that grows and ages, the Archive changes and should change. But unlike a body, it is destined to last. A living archive looks to the future, encompassing the risk of not being applied, understood or conserved. Its fragility leaves room for a possible and continued adjustment into something else, proposing a different history, a new archaeology.”