Laura Fiorio (1985, Verona, IT) is an artist working with photography, installation and relational practices. She studied Visual and Performing Arts (Venice), Film and Interactive Media (London) and Social Work through Art (Berlin). Her projects, developed through choral narratives, interact with existing archives and materials, questioning the power dynamics embedded in the editing process of images as memories, their institutionalized use and hence their critical and subversive potential. Fiorio’s research focuses on liminal situations, where the private sphere becomes a mirror for the public space, interrogating possible causes and socio-political consequences of a state of transition. Her work has been internationally exhibited, presented and published independently or in collaboration with institutions including Triennale (Milan, IT), Architecture Biennale (Venice, IT), Mufoco (Milan, IT), Bevilacqua la Masa (Venice, IT), CeCuT (Tijuana, MX), Haus der Kulturen der Welt (Berlin, DE), European Center for Constitutional and Human Rights (Berlin, DE), Festival Internacional de Valparaíso (Valparaiso,CL), Onassis Cultural Center (Athens, GR). She has been a guest professor at the Universidad de Baja California (Tijuana, MX) and University for Arts and Cultures (Ulaanbaatar, MN), among others. Currently, she is a research fellow in Decolonizing Architecture at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Stockholm.

Laura Fiorio. Altars of the Everyday (Ewald, Playa Ancha), 2021. Domestic sculptural installation documented as photographic fine art print, Valparaíso, 2021 Courtesy the artist

Ginevra Ludovici: How would you describe your artistic practice? Where does your research come from?

Laura Fiorio: I started making art through photography, which I conceive more as a tool for research and observation than an end. Photography is a means to shape my curiosity, allowing me to branch out on various topics and aspects of daily life. It is a means of knowing, observing, and analyzing problematic realities that must be looked at from different angles to be fully understood. I am interested in the plurality of gazes and perspective shifts, which I try to enact not only through pictures but also using other media (installations, performances, or discussions). For me, these latter are ways of creating spaces to weave relationships, invite confrontation, and host inclusive narratives. I think that a series of photographs sometimes is not enough to develop a complex narrative, so I employ other strategies or materials which may be more effective in conveying the experience or perception of that particular situation. My artistic practice is highly collaborative because the pictures are always the result of interaction with multiple people actively participating in the photographic process. Recognizing the value of this cooperation and considering the outcome of a particular inquiry as co-authorial rather than authorial was an important moment of realization in my artistic path.

I began by photographing mainly architecture and landscapes by participating in campaigns to document specific territories. I often found out that the most exciting things, such as the stories and interactions I had with the people I met, remained out of the frame, and I began to wonder how I could include them. For the past few years, I have been actively intervening in the photos I took, either in pre-production (creating staged images) or in post-production (with collages, cutouts, or drawings). I am very interested in the photographic image as an object because, by referring directly to reality, by imitation or absence, it can open up possibilities to question and reinterpret it deeply.

G.L.: This expanded approach is very interesting and it is also reflected in your educational background. You did not only train in fine arts but also new media and technology arts, art and social work, and carpentry. How have these experiences informed your practice?

L.F.: I think having had a nonlinear educational background has deeply inspired my interdisciplinary approach. Thus, flexibility and versatility have become a very part of my artistic practice, which, as I said, is more focused on the process than the outcome.

Continuous experimentation, relationships with people from different disciplines and contexts, and sharing diverse knowledge are ways to get out of the rigid compartments in which people, things, and disciplines are often categorized.

This contamination, in my opinion, is fundamental to making art but also living the everyday in a sustainable way by creating culture even outside of contexts and circles dedicated to art.

Many of my projects took place in unconventional exhibitionary settings, like houses or public spaces, and then, in some cases, also exhibited in museums, galleries or art spaces.

2. Laura Fiorio. Vanishing Lakes, Bangalore, 2018

G.L.: Throughout your career, you operated in many geographies, in many cases involving different communities. I am thinking about the projects Vanishing Lakes in Bangalore, India, and La Border Curios in Tijuana, Mexico, among others. Could you tell us more about your approach to conducting your research? What challenges did you encounter when dealing with sensitive topics in far-away settings?

L.F.: Both projects originated from the invitation and support of the local Goethe Institut, which, by my initiative, included close collaboration with the local cultural scene and related territorial issues. Meeting and exchanging are essential to me, as my approach as an artist-in-residence is not to produce work about a certain reality, but with the reality I encounter. Being in a listening disposition and exploring with people who live in that geography daily is, therefore, crucial to avoid presenting narratives dominated by westerners and mediatized stereotypes. The knowledge of a particular geography can only begin for me when my body is in that specific place and interacts with some of its dynamics, whether personal, cultural, linguistic, or urban.

In these two specific projects, we worked on territorial issues that crucially affect people’s lives. In the case of Tijuana, I looked at the border as a physical barrier, considering the history between Mexico and the US and the most recents narratives attached to it. Indeed, when I was working on this project, US President Donald Trump was publicizing the construction of a wall even higher than the existing one.

While in the case of Bangalore, which is also called the Indian Silicon Valley, the focus was on the wild gentrification process ignited by the tech industry, which was seriously harming the original urban fabric, specifically the lakes that were once very important resources not only for the environment and the economy but also for sociality and religion.

The initial methodology was similar in both places: I involved students, NGOs, and local experts – such as journalists, human rights activists, artists and urban planners – to participate in a workshop on these issues. The idea was to engage with them, establish connections and create a collective discussion before developing the artistic project.

After this initial phase, the projects took different directions based on the group dynamics and interests.

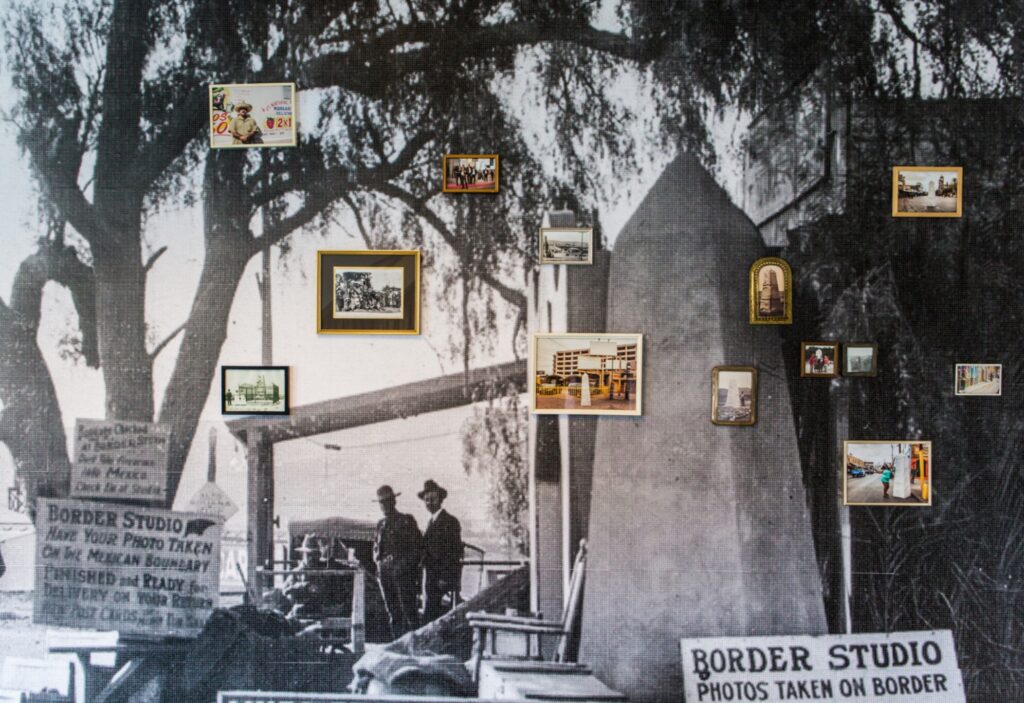

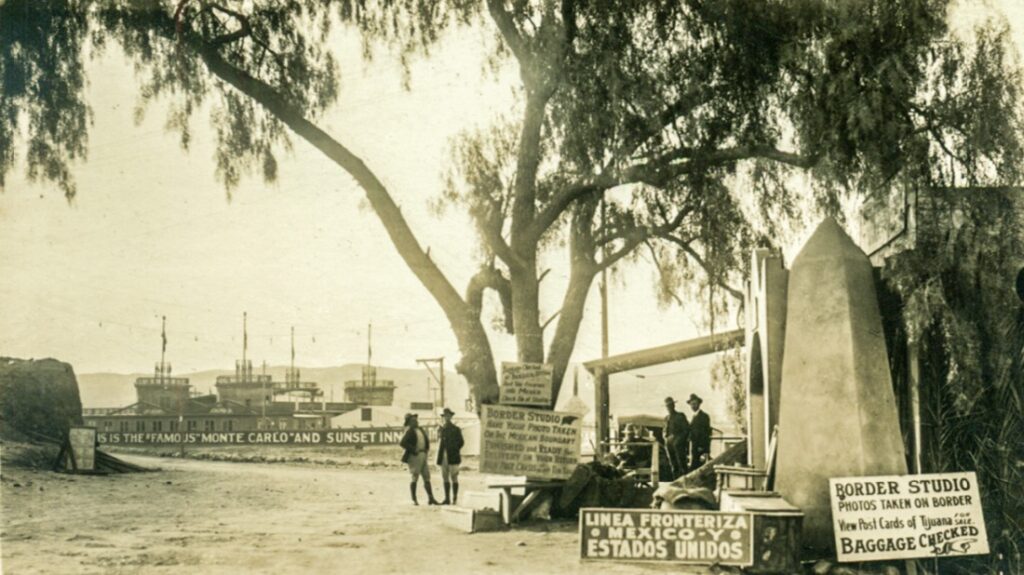

In Tijuana, for example, there was a lot of participation from the migrant community. Starting from archival images depicting Mexican photographers taking pictures of tourists near monolithic border stones, we decided to reconstruct a piñata in the shape of a monolith and move it around the city. The idea came from a story the archive director told us: that stone in the photo was fake. The photographers had built a set because the border line at the time had been moved, so they needed a visual reference for American tourists who would buy their portrait’s postcards with the milestone.

Working in collaboration with a migrant shelter, we decided to follow the footsteps of these ambulant photographers and reconstruct a monolith of papier mache in the style of a piñata, which we then moved around the city, especially in the border areas, where there are people endlessly queuing up to cross to the US. After this intervention, we decided to operate in Plaza Viva Tijuana, a transitory non-place next to the Mexican border which is the first place to be seen entering Mexico and where many migrants live. We temporarily converted an abandoned area at the plaza into a workshop space to organize activities and an exhibition discussing the issue of representation of such a place. During the two-day event (an opening and a finissage), we also organized a moment when the replica milestone was destroyed, like all the piñatas, symbolically beating the physicality of the border. The space has to this day remained marked by the exhibition: the traces of the posters are still there. Indeed, when I came back a few years later, I was amazed that they had remained, and recently someone sent me some photos, so they are still there somehow.

In Bangalore, instead, we gathered people’s stories of where the lakes once were and followed the traces still visible (for example, in the shrines or large trees that were used to chill in shadow and perform morning rituals). After that, we created a map of what is now in these places: mostly construction sites and hyper-modern buildings designed to house start-ups and tech agencies. During this experience, I collaborated with a collective of programmers and hackers who developed hardware and software technologies to increase culture and education in rural areas, as well as create a digital archive of oral documents related to the land.

We recreated a virtual map of where the lakes once were. The idea was to reconstruct those places through augmented reality through the testimonies involved, mixing archival photos, renderings and current photographic material. This project has been on hold for the pandemic, but there is the idea of continuing to implement it: it will be interesting to see how the areas considered have changed a couple of years later.

G.L.: In 2021, you developed a photographic series titled Reinventario, which was exhibited at the MUFOCO – Museum for Contemporary Photography near Milan. Based on the inventory of the disused Bormioli glass factory in Parma, the project focuses on material evidence from the past to create new narratives for the future. What is your approach when working with archival material that is often neglected or forgotten? Which strategies do you use to make it “living” and significant for the present?

L.F.: The contemporary discussion on archives is very interesting because it is related to the issue of interpretation and questions about who has the role of editing, preserving, and handing down certain narratives as opposed to others. The historical, ritual, or cultural value of particular objects, people or representations is not only in the hands of photographers and artists, as any picture can be reinterpreted again depending on who reads it, as well as who writes it. Also, in addition to reading and watching, it is important to communicate, tell and listen, as the oral and relational culture is mostly not visible.

So when I discover an unpublished archive, a small treasure in someone’s home or somewhere out of the spotlight, I like to listen to the stories of those who reflect their memories in those materials. It is precisely those stories that inspire the creation of new narratives.

To reinvent (“reinventare”) means to revisit something, to take possession of the narratives of that specific situation and make them one’s own, most often giving it a new, very personal meaning. By reinventing, one often discovers something that has been forgotten, hears untold stories, and gives a different use to something that had been created with other intentions. Reinventario takes inspiration from this reinvented imagery but adds a new layer by also focusing on another aspect that is contained in its name: the action of inventory.

Such a word has a much more technical and methodical meaning, indicating a meticulous and repetitive activity requiring patience and precision. It refers more to the archival and cataloging field but also commercial slang; it relates to the availability of certain goods, property, or movable and immovable assets of an institution. An inventory has more of the function of certifying, documenting, cataloging, and legitimizing.

Putting these two apparently incompatible actions together, I questioned our relationship with an iconographic heritage, particularly with the photographic image, which is both a document and an invention. I coined a somewhat irreverent term that goes outside the box and unhinges institutional semantics.

But above all, I questioned the integrity of a dominant story, opening up the possibility of many other parallel narratives that express themselves with different media and languages.

The creation process of Reinventario was very organic, fluid, and spontaneous. The former factory workers have an association called Medaglie d’Oro Bormioli, historically a title given to those who had worked for at least 25 years in the company. The group organized various leisure and after-work activities and was formed after a series of trade union struggles in which workers demanded more acceptable conditions in the factory. After the company closed down, the association survived and the relations of friendship and solidarity between its members remained. They have been meeting as they did before and organizing initiatives together. When it came out that the factory was going to be demolished, they worked to recover the movables, archives, and memories that were contained within the building. They also found a warehouse to store all that, and that would function as a new headquarters for the association. Actually, the work of collecting and archiving the images was not done by me, but they did it.

When they showed me their archive, I was deeply moved. I acted like a curator or a photo editor: I made a selection and started to digitize images and inventory objects, creating new connections and stories.

However, I still need to consider the project to be finished; indeed, the best is yet to come: we are working together with the Gruppo Medaglie d’Oro and other cultural associations in Parma on a hypothetical proposal for the museum display. The installation conceived for the exhibition at MuFoCo wanted to be an experiment to test various narrative strategies in the space, with the hope that the restoration work will proceed quickly to realize the design and occupy the space with a cultural and social center for the San Leonardo district, where the old factory was located.

G.L.: You are one of the fellows of DAAS – Decolonizing Architecture Advanced Studies, a postmaster course at the Royal Institute of Art in Stockholm, Sweden. As part of the course, you have been doing fieldwork in Borgo Rizza (Sicily), an abandoned rural settlement founded during the Fascist era, intending to reactivate it. Could you tell us more about this experience?

L.F.: DAAS research is mainly based on case studies related to Italy’s colonial past. Generally, when speaking of colonization, we look primarily at non-European territories. In the Italian case, however, the colonial campaign that began at the dawn of unity toward Africa also affected the newly formed, fragmented, and highly diversified Italian territory. Talking about “internal colonization” and the southern question, we move away from the issue related to the nation-state to focus more on the concept of forced modernization of any territory that does not correspond to any canon of development or civilization. The collective research takes its cue precisely from the Entity of Colonization of the Sicilian Latifondo to analyze the dynamics of violent occupation of a territory dictated by propaganda and demagogy. A kind of violence not necessarily visible but systemic, which can be found as a pattern in overseas realities as in many everyday moments.

I am particularly interested in this research because when we talk about decolonization, we always think of an “other” from exotic and distant places, with which, many times, it is difficult to identify. Here we can bring the decolonial practice back to the everyday to unveil those dynamics that are not at all past, that should be unhinged, and that are, many times, right in front of us.

In Borgo Rizza, we worked with people from the area and different backgrounds to ask what meaning these architectures have now. They were new towns originally built as grain collection and sorting centers in the Fascist era, never really functional except on a propaganda level, but which can take on, here and today, different meanings, from monuments and memorials to places of critical culture and decolonial practices.

I think the fundamental question lies not so much in the past as in the present of these places and architectures. Of course, it is as important to remember what these structures represent and what they have served as it is to encounter strategies to disrupt those same dynamics and prevent them from being repeated in the future.

Personally, I have been working directly on my biographical and intimate sphere by researching the history of my grandfather, who was not only a fascist but had also been fighting in Ethiopia.

Collecting photographs and objects from my family archive and asking other people to bring their own images and stories on the subject, I intended to create a safe space where to talk about a difficult legacy, as well as awaken and raise the debate about historical amnesia that is not sufficiently addressed, on the contrary, responsibilities are often denied.

G.L.: You have recently participated in The New Alphabet School, a collaborative self-organized school for practice-based research born in the context of the Haus der Kulturen der Welt (HKW) in Berlin. As a final restitution, you presented your collaborative work, Altars for the invisible, which was inspired by a previous work you did in Valparaíso, where you created altars in people’s homes. What was your initial inspiration behind this project? What was the reaction of the people involved?

L.F.: I have always been interested in altars as ritual spaces of community, sharing and mutual care. I am very intrigued by the dynamics behind this form of remembrance, which I appreciated particularly during one of my first trips to Mexico.

In the Mexican altars, I saw a joyful and compelling way of celebrating, remembering and accompanying the invisible, something that is not present among us physically but which we continue to carry with us. As vernacular architectures created from everyday objects and dedicated to a particular person or many people, altars function as places for healing, mourning and connecting with ancestors, but also with the loved living ones who join us in this experience.

In Valparaiso, I was invited for a residency at FiFV, Festival Internacional de Foto de Valparaiso, for an edition that took the title New Dwelling. Inspired by the title, I worked inside people’s homes, thus, relating to intimate spaces and situations.

I worked initially with a group of women, which gradually expanded, meeting in each other’s homes with the agreement to reflect on the objects in that environment, give them a new meaning, and collectively change their arrangement. In the end, it turned out that we began to build compositions which we began to call “altars of the everyday”. The process was very beautiful because it evoked memories, but also of symbologies and rituals, and the compositions told a lot about the person inhabiting the space: they were a portrait of both the place and its soul.

Also, the idea of entering people’s homes not to “take” something (an image, an interview), but to leave a mark or create something unexpected was very interesting. At first, viewed with curiosity and a slight suspicion, many people would ask me beforehand to put everything back the way it was. Then once they saw the altar, they asked to leave it and sent me pictures months later with the various evolutions of the composition.

At the Haus der Kulturen der Welt, I exhibited two of the altars’ reproductions taken in Valparaiso but doing things a little differently. This time we titled the altar to the invisible, which can be interpreted in many ways. In collaboration with two Mexican artists, Mariel Miranda and Ruth Renovato, we brought personal objects (ours and others) inside the museum, inviting the public to do the same and share their own stories related to that object.

The installation was part of the collaborative project “The New Alphabet,” an international unlearning platform, in its last edition, titled “Commonings”.

Site specific Projections: Found family pictures on fascist Architecture, documented as Fine Art Prints, Carlentini (Sicily), 2022. Courtesy the artist

G.L.: What projects are you currently working on?

L.F.: I am continuing to work on all the projects mentioned so far, which through interactions and collaborations, are further articulated.

Right now, I am working mainly on images from my grandfather’s archive and reflecting on difficult legacies and processes of decolonization not strictly related to that era and geography but bringing them back to the contemporary, to the discussion of human rights and politics today.

Currently, with this project, I have a collaboration with ECCHR / European Center for Constitutional and Human Rights in Berlin and an exhibition in collaboration with Remont Gallery in Belgrade. For both, we are thinking about how this reflection can interact with local discussions. In the case of Serbia, with the complex heritage of former Yugoslavia, while in Berlin, in relation with ECCHR, which works a lot with crimes and issues related to postcolonial restitution and reparation in Namibia.