Stefano Volpato: The collective show Pillows like pillars, which has featured your works at Barriera in Turin in May and June 2021, is over. This conversation is an opportunity to retrace our steps and discuss some issues that emerged, opening a horizontal dialogue among us, without the pressure from deadlines, from the event itself, but also from all the limitations linked to the pandemic we have been experiencing along the process. I would start with a transversal feature through all the interventions, which is strictly related to your artistic research and practices, even if they are clearly diversified. In my critical contribution to the exhibition catalog, I highlighted a common reference to a rather mysterious and opaque corporeality, its presence or trace, expansion or absence, its translation or dispersion.

Gianna Rubini: An important element of this common ground has certainly been the use of voice. I focused on my voice in relation to the machine, to the intelligent assistant Siri, then to the artificial intelligence. But all three of us brought this body reference, the voice, which represented a sort of narrative path within the walls of Barriera.

Maria Chiara Ziosi: The exhibition has changed continuously, also due to the extraordinary situation we have experienced in the last year and a half, and despite this there has always been a convergence on a common ground. For me it is interesting that the voice has emerged as part of it: it is a powerful device, but at the same time it is somehow an abstract one. Regarding the exhibition, the voice comes out to be paradoxical: it is something revealed but ephemeral, performative but mysterious.

Agnese Spolverini: Regarding the voice, I think it is a trend linked to a disappearance of the body during the last year. Moreover, in all our practices there is this dematerialization of the body, which turns out in other and unexpected forms. From this perspective, I think that the voice is one of the most evocative traces capable of bringing this issue back in the game.

Gianna Rubini: Yes, I think it is a tool that this year we have bonded a lot to, also considering the huge spread of remote communication with other people. Let’s think about the Clubhouse boom: it had just staked everything on the voice without images: detaching from a visually-saturated world to indulge in a voice that has no face, and its powerful, imaginative force.

Maria Chiara Ziosi

Oh hi, 2020

Agnese Spolverini,

Friends, 2020

Gianna Rubini,

Ehi, 2021

Agnese Spolverini,

Toothpaste Chronicles #3, 2021

Tengo un peso en el alma que non me deja respirar, 2019 La boum, 2021

Untitled (tears), 2020

Pillows like pillars exhibition view

Associazione Barriera, Turin 2021

Photo Studio Abbruzzese

Agnese Spolverini

Untitled (tears), 2020; Friends, 2020;

Maria Chiara Ziosi

Oh hi, 2020.

Pillows like pillars exhibition view

Associazione Barriera, Turin 2021

Photo Studio Abbruzzese

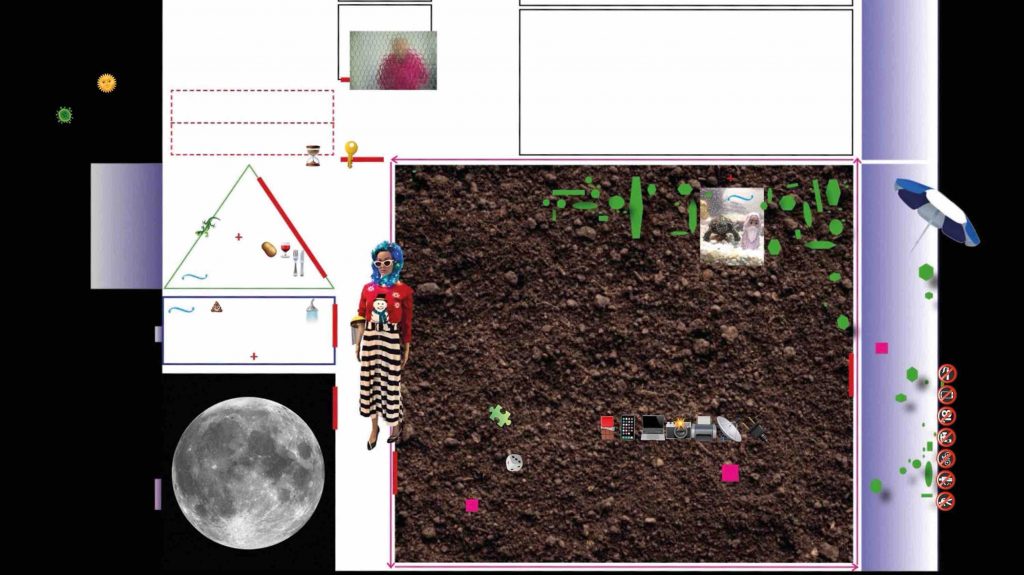

Maria Chiara Ziosi

Nickname generator, 2019

Gianna Rubini

Ehi, 2021

Agnese Spolverini

Toothpaste Chronicles #3, 2021

Tengo un peso en el alma que non me deja respirar, 2019

Pillows like pillars exhibition view

Associazione Barriera, Turin 2021

Photo Studio Abbruzzese

Stefano Volpato: I think there were quite different voices on display. The use that Agnese makes of the voice is more physical: it is her voice, as for example in La Boum. Gianna’s voice is lended to an alterity: an impossible subjectivity. Maria Chiara’s voice actually is not even present in the show: the one you featured in the work Songs from a rat hole is aseptic and androgynous.

Maria Chiara Ziosi: Above all, it’s not mine. We don’t know whose voice it is; the one you just mentioned is a work about fiction and deception: the story I try to tell is imaginary and fragmentary. I therefore worked on the non-recognition either of the voice by listeners or by the voice itself towards itself. There are five short speeches, sometimes hummed, sometimes spoken and each piece has a different intonation and a way of telling: sometimes more introspective, other times more evocative, others even more didactic.

Gianna Rubini: It seems that Maria Chiara and I made an opposite use of the voice: starting from a human content, you tried to use a less human voice, less identifiable – i.e. from the point of view of gender – I would say, somehow less linked to emotionality. On the other hand, I have started with a “non-human” content – the answers given to me by Siri during our conversations – and I used my voice to re-interpret them, without trying to simulate any digital or robotic nuance. Yes, there is the dramaturgical passage, in which Siri’s answers become a monologue, creating a narrative line – almost a mash-up starting from contents that come from a precise source, with a precise approach to the device, forcing the AI outside its comfort zone, to a foreign territory.

Maria Chiara Ziosi: The thing that seems relevant to me is that we both started from a written text: yours, Gianna, is a performative act that has a lot of the theatrical, even in the way it is performed; instead, among my references there is more radio play, for example. However, at the base there is a strong need to talk about self-exposure.

Stefano Volpato: Self-exposure, together with self-display, is another issue that has crossed the works on display, but more generally we could see it as a theme deeply concerning your practices. This reminds me also about the way I was involved in the project when I got in contact with Barriera: as a young curator, underlining the idea of something new, fresh, never seen before. This prompted me to reflect on how much putting your work on display involves displaying yourself. It seems to me that there is also a kind of youngness-ratio in this equation, strongly connected to the theme of self-exposure.

Maria Chiara Ziosi: Indeed, so it is. I think all three of us deal with identity and its narration. As far as I am concerned, it seems this revolves around recognition, self-narration, self-identification and therefore also around showing off. As we have already told in the past, Pillows like pillars was an exhibition that also tended to hide.

Agnese Spolverini

Untitled (crumpled), 2019

Photo Alessandra Draghi

Courtesy the artist

Agnese Spolverini

Untitled (crumpled), 2019

Photo Luigi Varacalli

Courtesy the artist

Stefano Volpato: Is there a contradiction in this?

Maria Chiara Ziosi: Yes, there is; but I think that if the contradiction is on purpose, it may be the best way to make something understood. For example, if you want to talk about something fake, by doing something even more fake you could unhinge some logic. In other words, talking about the difficulty of self-narration by hiding yourself: this points out a difficulty without having to tell it.

Gianna Rubini: Regarding this, an interesting article on intimacy as a conundrum comes to my mind, by the Italian philosopher Bruno Madera. He tells a short anecdote about Michèle Blondel’s paintings, which were all white, because white sums up all colors but none were visible. She was convinced, in this way, to be hidden from the gaze of others. But then she came to the opposite consideration, because “when people believe what we say about ourselves, then it was us who made up a box-shaped prison in which we lock ourselves without even realizing it”. Being exposed gives birth to fragility. So it is clear that when you try to show this intimacy you still feel exposed, especially if you are in a field open to the judgment of others.

Agnese Spolverini: There are works that if they do not experience the moment of their exhibition, actually they do not exist. In fact, I think some of them exist on the basis of their relationship with the other, not only with the place. It is precisely a relationship of continuous interdependence, the one between the moment before the exhibition and the exhibition itself. Some things and processes would not even make sense, if not to be fed to the other. I think our exhibition has not been designed for quick consumption. You can easily see around extremely captivating and amazing practices, instead Pillows like pillars needed a space for relationship: many works showed fragility. There was also a distracted audience, but I am afraid they didn’t really see anything: the visual part of the show was beautiful, but also very fragile, and needed time and attention. It is not a negative consideration from my side: it was nice to think about the exhibition discourse not in reference to a canon of perfection, but rather by orchestrating a series of notes, which do not present their own strength on their own, but cooperate to create a world together.

Gianna Rubini: Regarding my intervention featured in the exhibition, I have strongly perceived the audience’s desire to leave the space to listen to the recording after the visit. Many people needed to re-listen to it outside, to take it home: this is very interesting to me, as the work leaves the exhibition and institutional context by the will of the public, not the author.

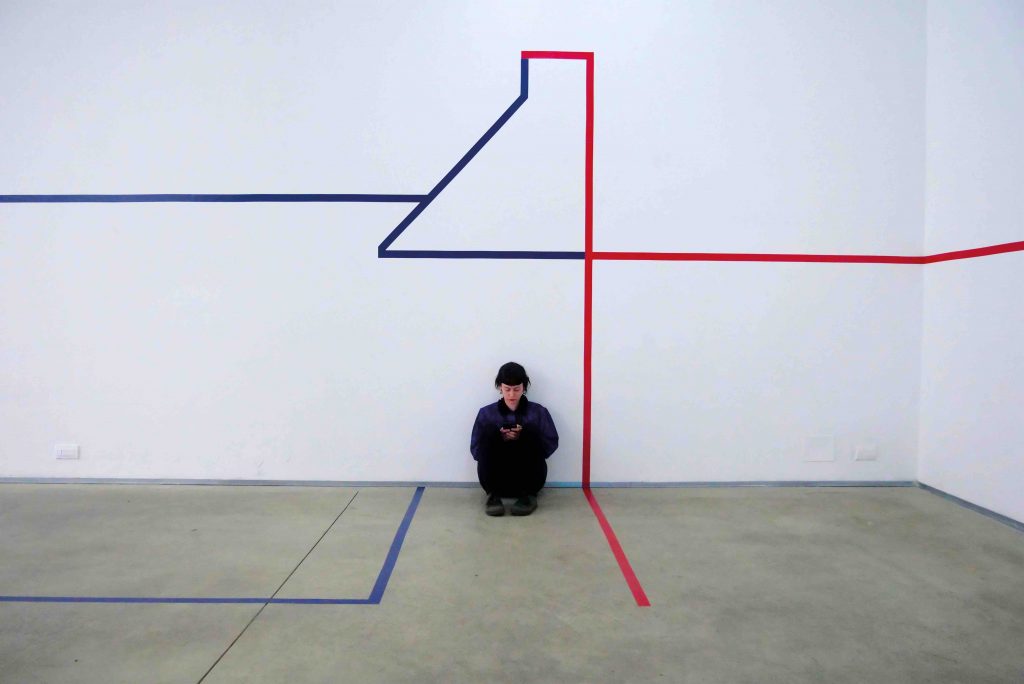

Stefano Volpato: Together with the powerful concept of notes as a display strategy, I think this latter openness stresses the vision of the exhibition project not as something finished, which ends around an object or space, but that can continue and expand. I also think of the scenography that Gianna created for Ehi, in addition to the recording of the monologue: an environmental intervention with a common material, the colored tape. It modified the exhibition space in a simple way, opening it up to the imagination in a very playful way; I am thinking of Maria Chiara’s works that found a different dimension with the public in the moment of the listening session. We have seen people living in the exhibition: I really got the impression of a feeling of domesticity inhabiting the moment, rather than a series of objects and interventions simply talking about it.

Maria Chiara Ziosi: Here the object also returns as a trace. When I think of an object, I think I’m simulating the trace of something. Talking about a trace is problematic, because it is something that refers to a previous experience, i.e. a performative act. Instead, I usually start from the idea of simulating a trace in some way, at least for these works on display. This simulation of a trace then gains strength in the exhibition moment.

Gianna Rubini, Ehi, 2021. Installation view at Barriera. Photo Studio Abbruzzese. Courtesy Barriera

Gianna Rubini. Colored cages, 2018. Digital image

Courtesy the artist

Gianna Rubini, Home, 2021

Digital image. Collaboration for Cartografia dell’abitare by Annalisa Zegna. Courtesy the artist

Stefano Volpato: Let’s focus on a word that Gianna mentioned a little while ago: intimacy. It is a mysterious, powerful concept, on which we have worked intensely…

Agnese Spolverini: …and that, by exposing itself, it apparently contradicts its nature. I am thinking about the exposure of intimacy: it is almost a paradoxical attempt. The moment you open it, beyond its dimension which is then an elusive, secret one, it becomes an impossible attempt. I feel it very much as a necessity to create closeness. But, again, it is quite paradoxical. It reconnects with the exposure of the self. The need to always expose a discourse on intimacy also tells about the collapse between the public and the private spheres. Everything overlaps, a little confusedly: it seems to me an attempt to cling to something.

Gianna Rubini: So I ask myself: is it possible to create intimacy and how? Is it something very private, or even public?

Agnese Spolverini: In my opinion, intimacy can also be shared. It is not just mine, something that belongs to me, but it certainly cannot belong to a very crowded audience. Perhaps the challenge is to make an audience intimate.

Maria Chiara Ziosi: There was an interesting question, in the same text by Madera quoted above: “is it really possible, and how, to see intimacy as a disclosure of oneself beyond role masks?”. It is clearly a political discourse, bonded to the way identity is fluid – not only the exposed one but also the personal one. There is always this contradiction in wanting to remain unknown but, at the same time, feeling the need to be someone. To be recognized, but without claims of any kind. I reflect a lot about what we tell each other to identify ourselves. And believing or not in something that we talk about or we are told by others. So, in this sense, the term “self” triggers a circle of personal and collective research that does not necessarily lead to a destination, to a solution. However, I believe it is important to describe this need. Perhaps it is a question of living and embracing the mystery; if being constantly exposed is actually a need, and also a normal condition – you find yourself in any place, at any time, in a situation in which you have to reveal yourself, or live in hiding – on the other hand there is also this need not to be all the way someone or something. And, as artists, the question is even more problematic.

Maria Chiara Ziosi. Oh hi, 2020. Pillows like pillars exhibition view. Associazione Barriera, Turin 2021. Photo Studio Abbruzzese

Stefano Volpato: All of your practices bring these issues to the table. That of Maria Chiara is linked to disappearance, deception and fiction; in the case of Agnese, it is carried out more directly, on the contrary by exposing herself in the first person and on personal basis; Gianna, on the other hand, mixes the planes: the personal is filtered by otherness and reassembled/reincarnated again. That emotional plane, which common sense would consider concerning a very private and exclusive part of us, is actually manipulable, subservient to other purposes.

Agnese Spolverini: There are a number of influences on this part of our existence, far beyond the most immediate and obvious example that could be advertising. Emotions, desires… nothing of what we consider to be part of our identity belongs to us; this is devastating, at least for me. Perhaps this is also why there is this desire to try to understand who one really is, when this still remains undefinable. There is no “free zone”; there is only an attempt to create a free zone; the challenge is to create a new territory to occupy, but it is difficult, almost impossible, because I feel that nothing belongs to me, not even myself belongs to me.

Gianna Rubini: So what is remaining of what we call intimacy? Perhaps, to define the awareness of these conditionings. Personally, it seems to me that I often get to talk about this but starting from another point, for example from the deconstruction of gestures, words, superficial postures that we execute automatically.

Maria Chiara Ziosi: Whether it’s authentic or not, we’ll never know, intimacy is everywhere. Everything represents an act of violence towards this aspect. Of course, here the digital returns, the machine, because everything is delegated to something that makes you produce content that seems intimate, but it really isn’t.

Gianna Rubini: We are the result of other mechanisms. I felt an urgency to bring out the research linked to Siri, perhaps because of its punctuality with respect to the enormous theme of the invasion of every aspect, every moment of our daily life …

Stefano Volpato: … and the almost utopian attempt to somehow try to stem it.

Gianna Rubini: In that work, Siri gives its voice to me, indirectly. What is “mine” comes out of her answers that originated from my questions. In some exchanges we have had, it has really been like handing over your most personal and private part in the hands of a stranger.

Stefano Volpato: Perhaps in a too naive way, I imagine the circumstance of an exhibition as an opportunity to express oneself outside of pervasive dynamics, although within a culturally constructed framework: a moment where one can be naked, according to one’s own rules.

Maria Chiara Ziosi: However, it may seem like a territory where passivity and inert exposure reign. On the other hand, if it is an aware process, this act of disclosure of the naked self may say something; in this sense, intimacy is an active, political territory. Speaking of identity and hiding, it can seem a passive way to bare fragility, when instead this gesture could tell us of a choice: the attempt not to box oneself in one’s work. Something not aimed at oneself but that opens to dialogue. For me, disappearing or becoming evanescent is the way to focus on this: it is not an escape. That is why the moment of exposure and exhibition is important, as it is open to sharing. Can opening an exhibition and expanding it, like the work we did for the catalog, or with this conversation, be an example of how we all work?