By incorporating the multidisciplinary studies of western ideology and eastern philosophies, Hobbs ‘work continues to delegate the visionary archetypes that preside within postmodern societies showcasing his work in a way that steers the public’s attention away from unethical logic structures into a diverse awareness of the archaic customs of past civilizations. Adopting conceptual and minimalist conventions, Hobbs distinctly feels each piece is devout in provoking the synergetic potential between humankind and the plant kingdom. Throughout his dharmic influenced practice, he has shown strong advocacy for allegiances to obscure plant medicines as tools for personal growth and introspective vocation. Using ephemeral materials , such as plant matter, mushroom spores, and dehydrated animal limbs, his work continually demonstrates the delicate relationships we form in all biological systems, and how they can mislead economic and social aspirations. Now, with a better understanding of human subjugation, Hobbs works with within nature and galleries around the world using installation, sculpture, sound and happenings.

Francesca Pirillo: How did you get into art and what are your artistic influences?

Royce Allen Hobbs: I have been making art for as long as I can remember beginning with drawing, and then later, removing myself almost completely from conventional artistic practices, to a more focused attention on bonsai and blacksmithing well into my mid twenties. For many years I gave up the pursuit of art; believing there was no place for it in a spiritual practice, which I was immersed in at the time. The only thing that brought me back was stumbling upon the conceptualists: Kawara, Brouwn, Opalka, Kosuth, among many others.

Seeing works by these artists completely reshaped my understanding of the world around me.The influences in my work, I feel, come from a longing to dive deeper into the authenticity and mystery of our predicament…questions, I suppose, pertaining to the enlightened state, suffering and the evolution of symbiotic relationships. What has always fascinated me is the space in which artists exist; we can easily stare for hours if adequately in tune with that space into tapestries and dull textiles, or the legs of a wooden chair and be content with their intimate qualities. But, at the same time, be displeased with the current systems surrounding their placement within society.

F.P.: When and how did you begin performing?

R.A.H.: I began performing in death metal and straightedge hardcore bands as a vocalist in my late teens into my mid twenties. Although the passion and closeness that emerged from the dark venues, was like nothing I had ever seen before, it was the violence and hatred that appealed to me. There was deep love and compassion right out in the open, an all-in-one collapse of conditioned logic, to me; this was art disintegration, and aggression.

After leaving the metal scene, and experimenting with hallucinogens, I began work on biological locomotion, fixated within the context of art, through my performances with mushroom spores.

F.P.: Tell us about The Garden performances.

R.A.H.: In The Garden, I wanted to demonstrate our inherent ignorance when dealing with drug use in western societies, and perhaps, form a commentary surrounding the truth of machinery for higher orders in nature.

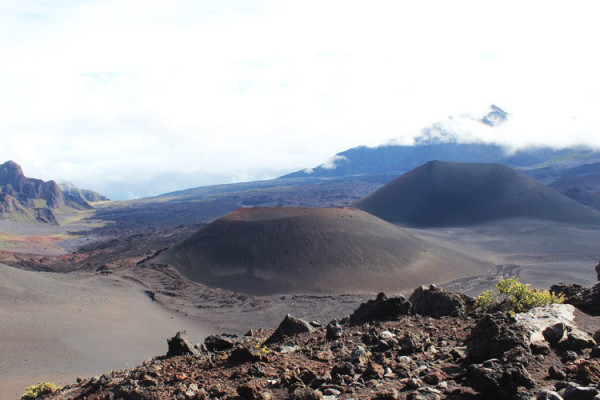

They are an ongoing series of solitary nature walks, in which, I use my body as a vehicle for psilocybin containing mushroom spores. They came about from my interest in some of the pioneering land artists or artists who worked within nature in the 60’s and 70’s, such as Hamish Fulton and Richard Long, and a few others, that would present text based wall and book works describing the experience of walking and being in nature as potentially a new art form; putting emphasis upon the experience, rather than commodity. This fascinated me, and opened up a world of possibilities. No longer did I feel the need to attach myself to the conventional studio practice.

F.P.: How would you describe your subject matter?

R.A.H.: I like to see it as a total collapse of self; of expectations, and a predetermined trust in art’s ability to function or influence according to stature; the grandest blunder of consequence. There are many themes and premises that can be used to describe my work, but the only one understood by myself would be ego-death, and a general distrust in academia. I am an advocate for people of knowledge, not simply ‘knowledgeable’ people. But somehow, it always manages to find it’s way back to the surface the cultural façade and we are left with the robbery of ‘Is-ness’, of ‘Being’. we are left with the robbery of ‘Is-ness’, of ‘Being’. The problem is, we ought to see the folds in our trousers and dresses as infinite and sufficient in their Suchness, but we never do. It is humbling to me; if I am in New York and see a piece by Duchamp, or maybe an Andre, to ask myself how it would make me feel if that was the only reason I came to New York. There are many vistas to be explored in these spaces, but in my mind, and in my work, ‘disappointment’ seems to be the only beneficial model to be engaged in to allow me to get to the substance of art. The truth.

Installation Psilocybe Stuntzii spores, knit sweater

Installation Psilocybe Stuntzii spores, knit sweater

F.P.: Could you talk about your interest in relationship-confrontation with nature?

R.A.H.: Relationship is nature. Every flower and tree on Earth has made a pact with some sort of separate entity, in order to assist it in transporting valuable information faster and more efficiently than they can from one point to another. The ferns use the wind, or the passing of a rodent, to spread their spores all over the forest floor; some spores travelling thousands of miles before establishing a new population in a new forest. Whether the rodent is conscious of this pact, their roles as couriers is what I am concerned with.

F.P.: How do you transport the idea to the object?

R.A.H.: The idea is already infinitely the object. I open myself to it and present as much as I can. I try to stay away from being to abrupt with presentation because real epiphanies seem to always be right in front of our faces, hiding in ‘plain’ sight. And it never has a description sheet or treasure map. This can be very difficult, and in turn, requires a great deal of time and work, the very thing I criticize in my work.

Installation Mask, cot, sprouted potatoes

F.P.: Can you talk about the knit sweater series and the idea behind it?

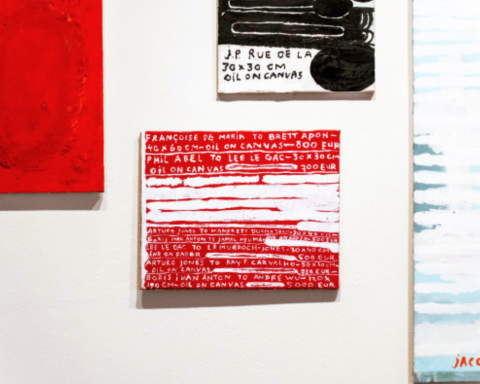

R.A.H.: The knit sweaters contain spores from selected psilocybin contain mushrooms, each sweater hosting a different species listed in the title of each work.

This is an ongoing series that, similarly to The Garden pieces, are also a critique of western drug policies. The basis being, uninformed scheduling of an extremely beneficial medicine into criminalization leaves me, and millions around the world, with a healthy distrust in the propaganda being fed to us through media and mouths of egotistical politicians.

The ready access to information we have today has given knowledge back to the people. And the more the governments try to repress this information, the more they themselves reveal the hypocrisy. Some of the best places to find hallucinogenic mushrooms are right out front of courthouses and police buildings. As the police try to punish the so called ‘criminals’, the spores from the mushroom, or ‘drug paraphernalia’ as they call it, are already attached to the clothing and evidence bags of the actors in this absurd drama, finding the perfect substrate in the landscaped mulch beds surrounding the government buildings. By trying to suppress it, they cultivate it.. When people see the sweater works, they are not only seeing a sculpture, that they may or may not use in their life after leaving the gallery context, but they are also taking with them the perfectly legal spores of a consciousness expanding mushroom, criminalized by the very system they are told to trust; a double narrative, seen only if there is an adjustment to the common perception of scale. An Everest within your hand, as it is.

F.P.: What role does the artist have in society?

R.A.H.: To be a mirror for the public; to impose primed mythological structures and mystery upon objects alleviating suffering. I also think it really just depends on what kind of work you happen to be making at the time. The folds of draperies lit by morning sunlight will always contain within them, a wilderness of perpetual modulation, and it’s the artist’s job to live in these spaces of light and darkness, to reveal the utterances of those wondrous states.

Sculpture Pipe, satin paint