The dialogue that we propose with the American artist David Bernstein is aimed at bringing out the fundamental knots of his work, through a comparison on the operating methods and the research philosophy that has led him over the years to consolidate a relational work that involves handmade objects, people and spaces both public and private in a redefinition of what we could call relational art. David Bernstein (1988, San Antonio, Texas) is an artist based in Brussels and Amsterdam who makes objects and finds ways to activate them, creating situations that serve as starting points for stories and performances. His projects deal with a range of subjects: psychology, wellness, fetishism, and spirituality. Next to his individual practice, he collaborates with a variety of people especially with his cosmic cowboy collective, Self Luminous Society.

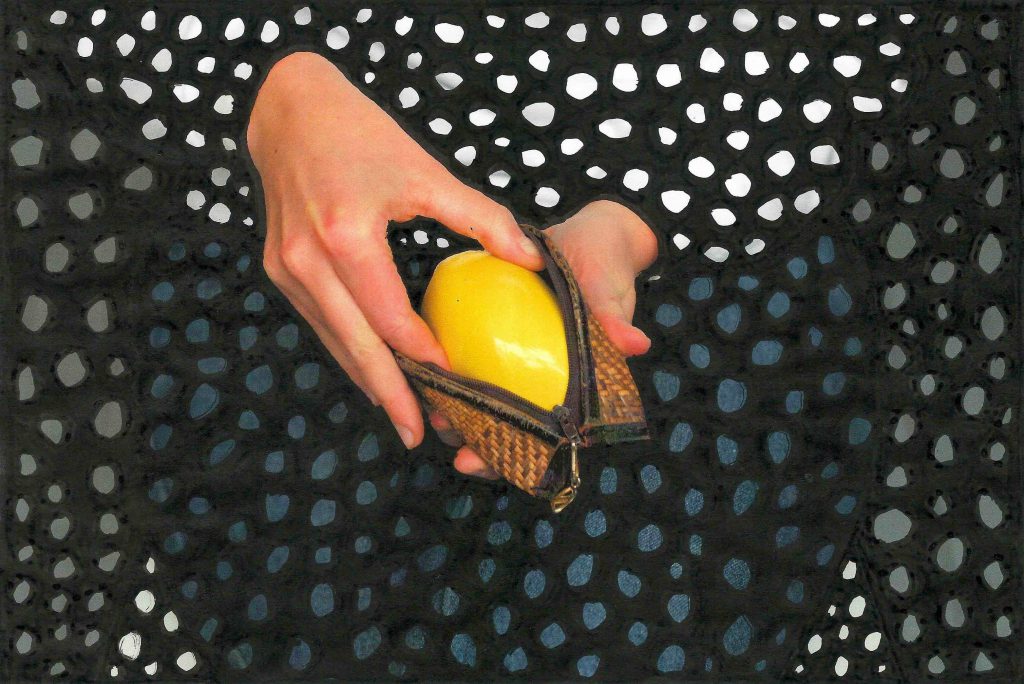

Something To Hold On To , 2019 Presented at SculptureCenter, NY, USA Photo Kyle Knodell

Fabrizio Ajello: The words ‘thing’ and ‘object’ have different meanings both in Italian and in English. Things are in a certain way living objects. There is a daimon inside. Daimon is the old Greek meaning of an entity between humans and gods, and at the same time it means deliver, spread, in relation to fate. In the southern tradition things can save and at the same time ruin individual destinies and entire communities. Things can also be devices that generate legends, tales, bringing back old memories and indicating future trajectories.

David Bernstein: Well, to be honest, I don’t think so much about the linguistic difference between the words ‘thing’ and ‘object’. As far as I know the difference is that when you say the word ‘thing’, it can be anything: ideas, words, colors, or physical things. And the word ‘object’ is more related to physical / tangible things. There was a moment in which people were interested in Object Oriented Ontology, I remember it was in vogue when I was studying from 2011 to 2013. Graham Harman was very popular, but for me, I was mostly thinking about how I could make fun of this philosophical trend. l was interested in how humor could free us from the seriousness of the subject but also shift the way of thinking about it. For example, I made a sculpture of a wooden spatula, a kitchen tool that was flipping inside of itself. This work is related to the concept of ouroboros, the snake that returns to itself by biting its tail, but at the same time I was thinking about the ontological object and the expression of a thing that speaks. I wondered if a thing speaks, does it ever talk to itself? In a way this was about an introspective object, but also about the humor of talking to oneself, like a crazy person does while walking down the street. Obviously my Spatula is a formal exploration, but at the same time it’s a linguistic game. It’s part of the thinging process, which is an idea that the artist Jurgis Paškevičius and I developed in a text we wrote together in 2012. Thinging is about thinking with things or the production of thought by things and how this affects the way we perceive what surrounds us, and how it could change things in an endless process of thinking and making. This text was also a way for us to explore text as something tangible. So, for me it is not important the distinction between objects and things, but more how we relate to them, how we produce meanings, emotions and associations from things. I’m interested in apperception, the psychological term for how our perception is influenced by what we already know. I experiment with apperception through narration, manipulation, reminiscence, and all the possible connections.

Something To Hold On To , 2019 Presented at SculptureCenter, NY, USA Photo Kyle Knodell

F.A.: So things themself do not exist, in a certain way? Are they already generated as thought? We manipulate and use them with respect to our apperception?

D.B.: I think things exist, but I’m also interested in the Buddhist ideas around the illusion of the world we live in. It reminds me of a line from John Giorno’s poem God is Man Made where he says “Everything is delusion, the play of emptiness awareness and bliss”. But when we start talking about these issues on an abstract level, I immediately wish to find a physical and concrete way of dealing with things, because when we have tangible stuff in front of us, then we have to deal with all kinds of information that we couldn’t expect in the abstract world of thought. I also like the humor that comes from taking abstract ideas and bringing them into the physical everyday. It reminds me of a joke about the ouroboros, that I heard once from comedian John Hodgman. He said, on the one hand an ouroboros is a symbol for infinity, and on the other hand, maybe it’s just a dumb snake that doesn’t know what to eat. I like his joke but at the same time it is so banal. This banality is so inspiring, because you are shifting a metaphor by thinking through the logic of a snake. A friend of mine went with her young nephew to a museum, and while looking at a portrait on the wall, the nephew said that it was a painting of a man with no legs, because the painting was only showing the top half of the person! This way of thinking is radical, it takes seriously our framed condition in a framed world.

David Bernstein

I & I , 2021

Solo performance exhibition

Presented at Artist Club Coffre Fort, Brussels (BE) Photos Lola Pertsowsky

David Bernstein

I & I , 2021

Solo performance exhibition

Presented at Artist Club Coffre Fort, Brussels (BE) Photos Lola Pertsowsky

F.A.: Speaking of frames. We are surrounded by frames, squares or rectangles. Windows, doors, screens, tables. Today more than ever, with these continuous lockdowns, it would seem that reality has flattened out on the screens of PCs, smartphones, televisions. Our own thinking seems to have fallen into an unbsunstancial two-dimensional state. Instead your work revolves around the relationship between people as well as the relationship through objects. I think, for example, about your work Saunra of 2017. What could develop in the future after this constraint and this distancing?

D.B.: It’s an accelerating version of something that had already been in action for a long time. Virtuality begins in the moment that you close your eyes, and you start to imagine. If you talk with somebody that is not in the same room as you, it becomes an imaginative process. The same happens if you are reading a book or sitting in front of a computer. We are experiencing different limits and extensions of a virtual experience. It is very interesting what happens when the virtual interacts with the tangible, because it is never only a book, a phone call, a computer screen, since something else always happens outside the frame. I can hear the noises behind me, check my phone, have a hot drink. We DJ our reality, mixing continuously our perceptual dimensions. It happens when we are jogging and listening to music. Of course our phone today is the centralization tool for every-thing, but it creates a new relationship to the community through different network platforms. At the same time young people use it in a physical way, think about tik tok, with all the choreography and dances. It’s mediated through the phone, but it is still physical. We all still need to enjoy physical things in a tangible world. We need to eat, we need to sleep, we need to breath, we need to have sex with each other, we want to move our body. I don’t believe in the Matrix future where we will float in a bubble. Devices are not enemies to fight, but of course at the same time, we need regulations because these tools have power and can affect our lives tremendously. With my artwork, I don’t want to reject technology, but find ways of bringing together a physical experience of the world with virtual mediations. I do this sometimes in small ways by including a video or phone call during a performance, or listening to an audio piece in relation to a specific space.

F.A.: Most of the objects you made are rounded. Is it a choice by a softening of the forms? In Italian language there is a way of saying, a proverb that sound like this: to square the circle (quadrare il cerchio) and the meaning is looking for the ideal solution for a certain problem, but it also means trying the impossible, because the problem to be solved is too difficult and the search for a solution is only mere illusion.

D.B.: With my girlfriend Sophia Holst, who is an architect, we talked a lot about the concept of roundness. She studied in a Steiner school, confronting anthroposophist ideas where roundness is important as an aesthetic philosophical approach. She also made a work about roundness, turning a square corner of a room into a round corner. I liked this idea a lot and it made me think about how so much of the world we live in is rectangular and how that is often a result of tools and production methods. Sometimes making some- thing round can be a provocation, challenging our ideas of practicality and efficiency.

F.A.: About materials and influences then, I’m sure of the extreme meticulousness in the choice of the materials you use. Warm ones, cold ones, soft, resistant, smooth, rough. You work on things, but at the same time things change your way of feeling, of perception. So, how much is important manual work and choose the correct material for the individual object?

D.B.: I’m comfortable with woods, for example, it’s very warm, and not so toxic. I can work very slowly sanding it, feeling myself just like a sand-man while I’m working. I like the act of sanding something because I enter a certain kind of meditation and slowly it gets smoother and smoother. I also like the sand-man story, referring to the man that comes in your sleep to rain dust on your eyes to bring you dreams. Maybe I’m sanding to produce future dreams. Sanding with my hands is important for me because things change relating to my hands, which is absolutely different from using a machine. Machines are based on straightness, but hands are imprecise, producing irregular objects. I like the unexpected forms which relate to your body and imperfections. I often make mistakes and then I have to figure out how to deal with it, learning from it, or going in a completely new direction.

Self Luminous Society, 2020 Nappezoid Performance Contemporary Art Center, Vilnius, LT Photo Dainius Putinas

F.A.: While you were talking about this process I was thinking about Penone’s work Essere fiume of 1980. An attempt to create a copy of a stone smoothed by the river, trying to simulate the work of water and natural events. This issue of copies and the attempt to work manually to simulate a natural product has always fascinated me. What do you think about it?

D.B.: I’m really interested in that desire, and I think that a lot of artists are involved in that desire, to create a perfect copy of something that is unique in nature. I once took a wooden Buddha and carved away the outside to show an abstract inner core. I then took a second piece of wood and carved a copy of the first object. Does this new object also have the spirit of the Buddha? It brings up questions of authentic- ity. A friend of mine who studies mimesis said that in the moment you make a copy, you actually produce the original, because before the copy there was never a thought about something being original or not. But when the original and the copy are so similar, then you might forget which is which and you could be thrown into a situation of doubt. This is the case in a story artist Emilio Moreno told in a performance I once saw. He spoke about taking an important sentimental object from his friend, having a perfect copy made of it and then he returned the original and the copy to his friend but he didn’t indicate which was which, so the sentimentality became confused with the question of authenticity. I don’t know if his story was real or fiction, but it’s the idea of the story that is important.

F.A.: False and True. ‘In a world that is really upside-down, the true is a moment of the false’, it is a quote from Debord that has always fascinated me but at the same time left me baffled. I don’t really know what the truth is and I don’t know if I really care about it too. In my opinion, artificiality is already a natural character and is certainly a distinctive trait of the human being and his interpretative, narrative and productive process. When you talk about the power of things, immediately comes to my mind the power of the relics of the saints, especially in the southern areas of the world. The power of what remains. In the Catholic faith, especially the remains of the saints are so important that they are present in everyday Italian language. We usually say of someone that is really a decent man that he is a saint’s shin (uno stinco di santo) referring to the tibia of the saint preserved inside Italian churches as a relic. There is at the same time magic and irony in this double way of perceiving and using this space in which we deal with objects.

David Bernstein

The Water Party, 2019

Solo Exhibition

Presented at A Tale Of A Tub, Rotterdam, NL Photo LNDWstudio

David Bernstein

The Water Party, 2019

Solo Exhibition

Presented at A Tale Of A Tub, Rotterdam, NL Photo LNDWstudio

D.B.: Relics and ex-votos are records of something miraculous. Sometimes they are proof of the holiness, but the holiness is something that can never be proven. I am fascinated by the way we try to give weight, love and value to something that cannot be explained. We even build precious containers and enormous churches to house them. It would seem fetishism, but I am very interested in the power of these sacred objects, linked to an individual’s gratitude, feeding into that collective belief through a physical gift. I found an ex-voto online from Mexico where someone was thanking the Virgin of Guadalupe for bringing back his voice after he lost it when seeing an alien coming out of a spaceship! Aliens and Christianity, it sounds crazy, but why not? We are talking about stories and legends, some people believe, others not, but these stories and legends have the power to influence what we think, the way we make decisions. This leads to another fundamental question: What is our responsibility for the stories we tell and how we tell them? Is there an ethical dilemma of lying in art? I try to deal with these problems by exposing the mechanism of lying in my performance, making it clear to the audience that I’m tricking them. This decision is important because it brings them inside the story, breaking some barriers, and revealing that it’s all fiction, but a fiction based on real ideas and questions. It’s kind of like the placebo effect, where the medicine supposedly doesn’t do anything, but actually the power of suggestion does a lot, it can work better than some ‘real’ medicine. For example, I perform as an alter ego cosmic cowboy called Slim Denken in a collective called Self Luminous Society together with Marianne Theunissen, Juan Pablo Plazas, and Bernice Nauta. We are tricksters who tell stories and play with words. In one of our performances I start the story by inviting the audience to take a placebo pill while telling them that it contains no medicine. I like this tautological offer because you normally don’t reveal that a pill is a placebo, because that ruins the placebo effect. But I thought it’s a nice challenge to the audience because I’m telling them from the very beginning that I’m a liar, I’m a trickster cosmic cowboy alter-ego, but then I am also telling them the truth when I offer them the placebo pill. It asks the audience to trust me with their bodies, to ingest an unknown pill from a stranger. Of course some people were uncomfortable with this. I was a liar telling the truth, and the truth was that the medicine I was offering was false. In a way it returns to the ouroboros process, as we are eating the tail of our own doubts and beliefs.

F.A.: In Italian language we are used to saying: I give you good advice, don’t ever accept any advice. Anyway, we live in a metaphorical world. We speak with visual words, generating images while we are talking. Sometimes this unconscious way of expressing ourselves opens up unexpected scenarios, new interpretative opportunities. A strange kind of worlds in between, ambiguous, but generatives.

D.B.: Yes, we live in a metaphorical world, we produce metaphors, but what interests me most is when the metaphor leaves the plane of ideas to descend into the tangible level of things. As in my placebo performance, it was not just words or ideas, but something physical that could change or affect us. What is important is living the metaphor, which is also what happens in religion with many rituals.

In Jewish culture, we celebrate the holiday of Passover remembrering the exodus from Egypt, the passage from slavery to freedom. There is an evening event with a big dinner, but before anyone can eat, you must perform a lot of rituals, tell the story, and drink two glasses of wine. It takes a long time and you are getting a bit drunk and more and more hungry until finally you can eat the dinner. In a way, this waiting and hunger parallels the story of suffering that is being told, so you are embodying the story; physically feeling the ideas. It also reminds me of the book Emotional Design by Donald A. Norman that I read during my studies. The book divides our relationship with objects in three ways of experiencing them: the functional, the behavioral, and the reflexive. The first is about how the things work, “does this hammer put nails in wood?” The second is about how you feel during the action, “does this hammer have a smooth and sexy handle?” And the third is about a meta thought, what you think about the experience and what will you remember, “This hammer belonged to my grandfather and I think about him whenever I use it.” This third aspect of the reflexive has always fascinated me. I’m really interested in how to create physical experiences of art that simultaneously have meta layers of meaning. I try to do this with my work, the Saunra, which you mentioned earlier. It’s a sauna that I built inside of my Fiat Multipla. Inside the car plays the music of Sun Ra and his Arkestra while you sweat. I like the idea that this sauna is simultaneously a functional object, while having reflexive elements that make you think about the meaning of your experience. What does it mean to take a sauna in a car and especially this car which has its own story? And the music of Sun Ra is both relaxing and at other times full of chaos and thoughts on nuclear war. The work was meant as a healing space for our troubled times; a place of warmth, hope, and humor.

Between the Soup and the Potatoes, 2018 Chinese ink on inkjet print by Rosa Sijben, 29.7 x 21 cm

F.A.: Again I have the feeling that Saunra is a work that insists on a circularity, both on the point of view of a closed and circular space, and at same time on the peculiar moment, as you say, of reflection and relaxation. We never get rid of the ouroboros.

D.B.: I think it’s funny that we keep coming back to the ouroboros. I guess it’s the nature of the symbol! I think you’ve captured a real core in my thinking with this talk about circling, but actually maybe the core is not about the loop or the circle, but it’s really about the spiral. I’ve been thinking about the spiral again recently because of a master class I attended on rethinking / queering a Jewish ceremonial object called the Shofar (a spiraling rams horn blown on the new year). During the class, I started realizing that many Jewish objects have spiral forms, and when I asked the guide of the course about it, she commented that the spiral is an important symbol for understanding time in Judaism. Time is thought of as returning to the same place, but at a new location; a progression towards a better future. We tell the same story, but we are always seeing it in a new way. The circle implies returning to the same place, but the spiral suggests new perspectives. Perhaps it’s the ouroboros who is so stupid that when it goes looking for its tail, it can’t find it and instead enters into an endless spiral. Maybe this snake will spiral on in an unexpected direction, leading towards a wondrous unknown. Or maybe it will just become a vegetarian.