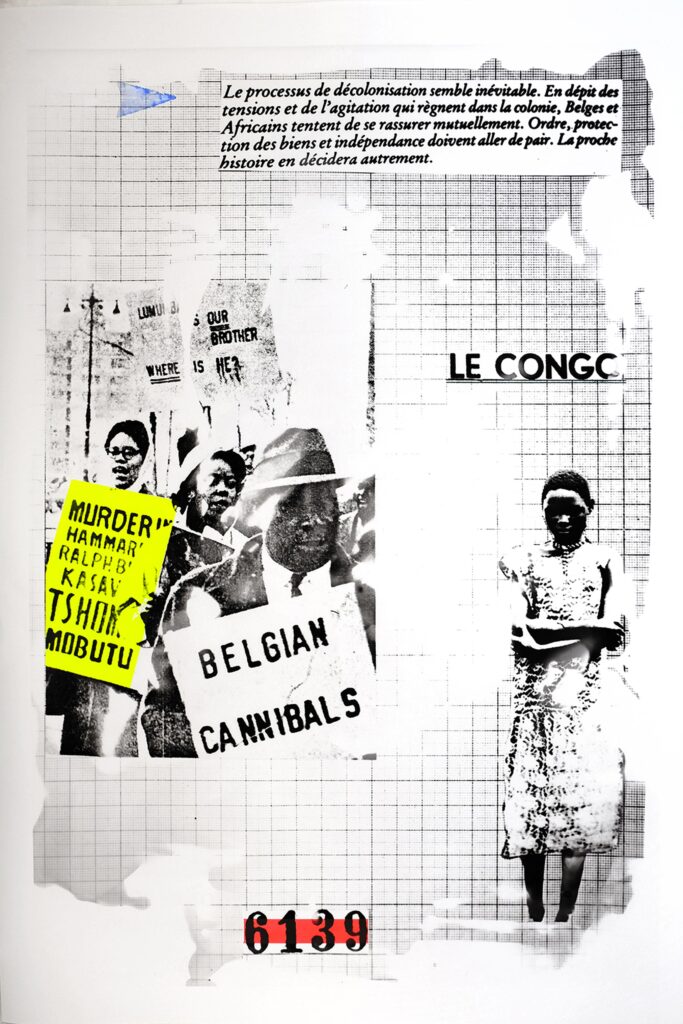

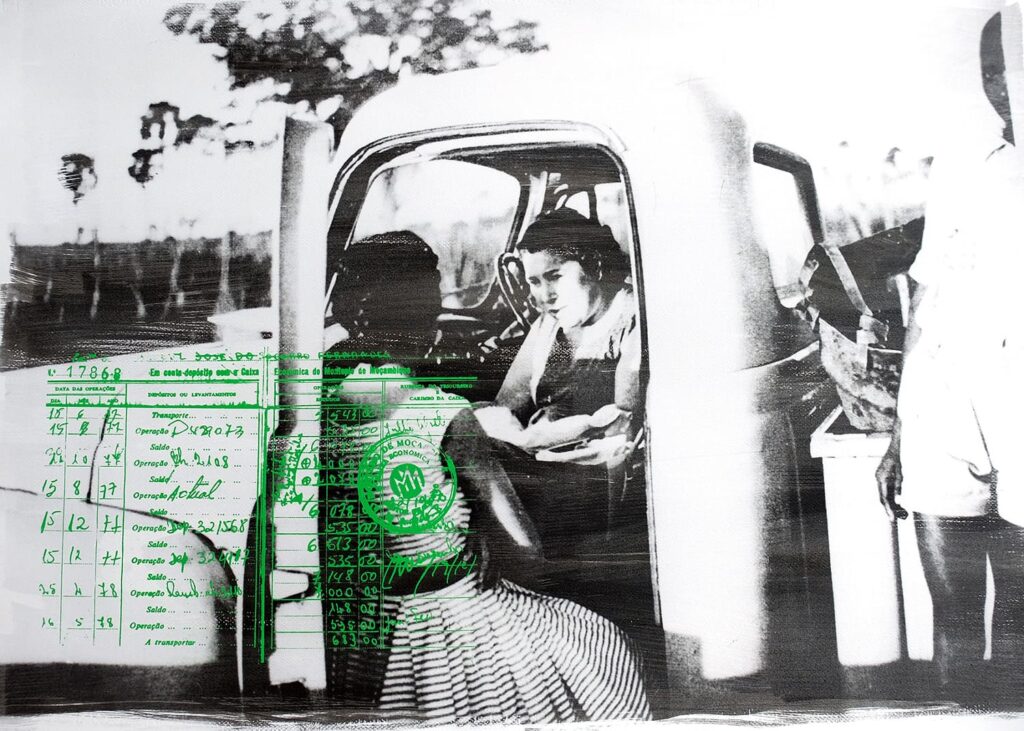

Délio Jasse (Angola, 1980) is an unconventional photographer. Délio assembles, collects, archives and recomposes, through a process of deconstructing layering images. A slow and careful proceeding that crosses cultures, his own Angolan one, and the transient ones in which he settles. His are narratives that draw on past and present history, particularly from colonial history. Drawing from the material production of objects (images, newspaper clippings, new and archival photographs), it returns a different reading and view of a specific historical fact. Compositions that become traces and memories capable of constructing new historical trajectories, both personal and collective.

Elena Solito: The archive is possible elsewhere to draw on, capable of constructing narratives by following intentions and trajectories. Tell me about your relationship with the archive.

Délio Jasse: My relationship with the archive starts from a necessity, that of telling the story from another point of view, the point of view of those who were colonized. Those who experienced colonization on their own skin, in this case we are talking about Ethiopia, tell a different story from the one told by the colonizers. The intent is not to forget the past: the problem is when we do not talk about things. It is necessary to talk about things, so that we do not forget them, so that we have them clear in our memory, so that we learn from them and tell others about them, so that we do not come back to the same mistakes again.

E.S.: Although photography represents the goal of mechanics and technology, you retain a very physical relationship with the object photography starting with the camera, the paper used and the printing process using particular methods.

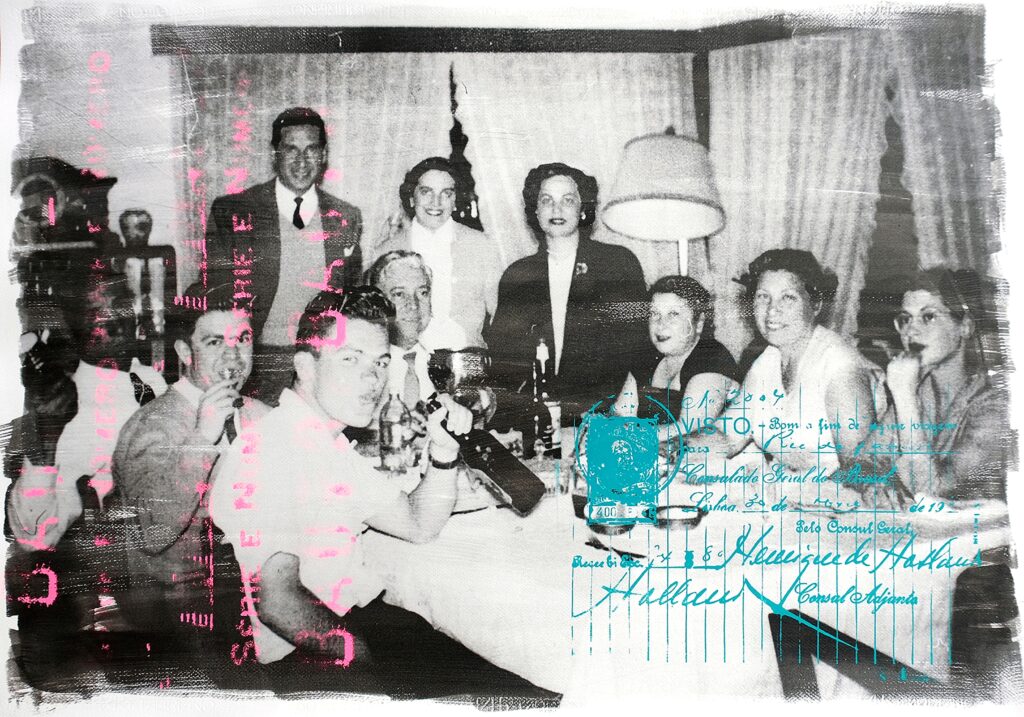

D:J.: I think the mechanism is photography: when creating a colony, photog- raphy was a fundamental means of building a narrative. At the technical level, as in documentary filmmaking, it is very important to use the medium you are working with well. I also specialize in printing techniques from the 1800s to the present day, to be able to represent and tell a story in a different way: when I want to tell the story from a different perspective, I change the technique. In this case, I have often used the technique of cyanotype and Van Dyke Brown, which are much more effective in representing the message. Starting from the shots I use, the colonial ones, I kind of invent a new shot: it is very important in my work, to be able to invent a “new shot” from the original ones.

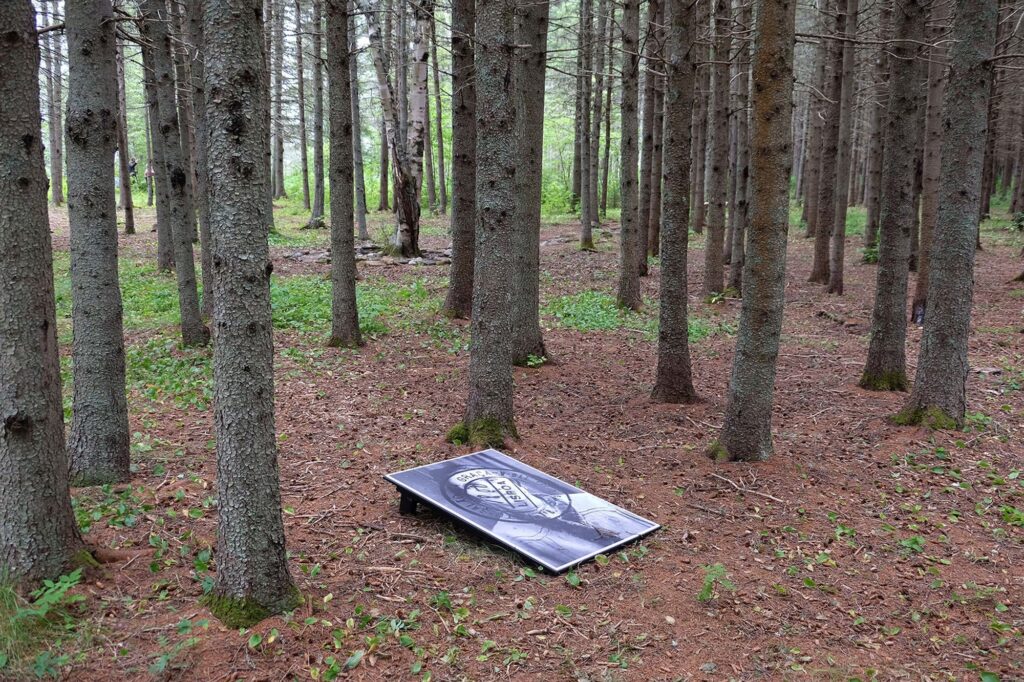

E.S.: In your practice, photography subverts its nature by becoming a malleable surface. The works are installed on boxes, projected, suspended in space. The photographic object acquires the status of an object with margins and boundar- ies that alters its natural two-dimensionality.

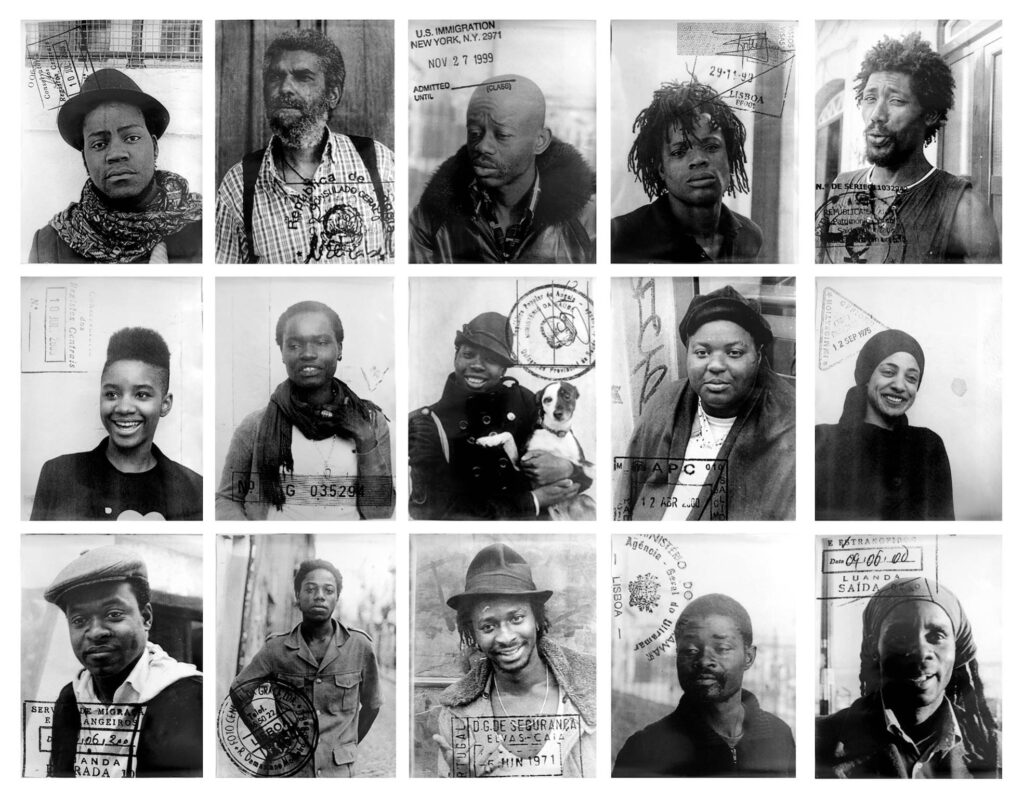

D:J.: Yes, the size changes everything. I want to bring out a tension, breaking the barrier of the frame, I break its parameters of the object we are accustomed to in some way: for example, working on passport photos – a photograph designed to be small, suitable for a document – I enlarge it, completely rethinking its spatial boundaries. I don’t use frames, I don’t care: this past I tell must be left like this, floating, unframed, as if stopped in time, like a stuffed animal. Like the textiles, which remain floating in the air, such as the story which is told over them.

E.S.: Not only color on monochrome fields (a reference to Japanese pictorialism photography), but also the incursion of stamps such as those used in documents. The latter are an expression of transient location, the passage from one place to another or the impossibility of crossing it. An inquiry into identity, boundary, the concept of geographic contextualization, physical displacement and the shifting of meaning through your work. Tell me about these projects.

D:J.: I think we always have to depend on a stamp, a signature and a finger- print to identify who we are, where we are going, what country we are going to, what we want to be surrounded by. This mechanism has very loud noises: every time we cross a border, the document has to be signed. We always have in mind this sound of the stamp that approves your entry, whether mechanical or handmade, this dry, precise sound that recalls how the system works, in a mechanical, automatic way. When I was living in Portugal, in Europe, in my early twenties, I had to wait a long time for these stamps to say who I am, where I’m going, what I have to be, what I have to do. I depended on a stamp to determine a justification, a pass, that had nothing to do with where I was going or what I was doing. In this case, in my photographic documents, I always need to stamp it, as if it were an action in which I say no to colonialism. I stamp my works using the same official stamps of the time, as if to make them official documents. For me it’s a bit of a game, which I like to put on the scale.

E.S.: I am very interested in the concept of displacement. Not only in a migratory sense, but with regard to history. History is a narrative-often written by the victors and with a judgmental and prejudiced gaze. I find your acting critically toward colonial history interesting. The archival work you do already involves a kind of critical selection of material.

D:J.: Yes, of course: those who win the war tell the story. However, war is the wrong territory: those who have the technical strength to do so win. I utilize archival photos, a vernacular archive, to highlight images that were not used for propaganda at the time. I use the image of the Italian colonizer in the day to day, normal moments. I am not interested in showing an official state visit. I’m not interested in showing Africans who are suffering, because all that was already seen at the time. I, as a visual artist, want to stage these photographs, to show what was not seen at the time. If someone were to come and give me a picture from an official visit, I wouldn’t care; I want to show the daily life of the people who lived there. I am interested in telling the personal memory, the one that few people know about. Not the collective memory, which has already been told over and over again.

E.S.: Professionally, you have exhibited in institutional venues (including the Angola Pavilion at the 2015 Biennale), in important galleries and younger ones, but also in an unconventional space such as Spazio Bidet. The mode is that of the showcase as a device that triggers a direct relationship with the non-specialized viewer. What is your relationship like with the cities that host you and in which you have lived?

D:J.: The Biennale and all the official spaces are very interesting. However, I prefer unconventional ones, like for example this big showcase, this big installation I did, where people would walk by and look at it without having to go into a museum, into an enclosed space. I like people to be able to enjoy art without neces- sarily having to go to a place designed to house a work of art. I want people to be able to come across a work on their way to work, on the go. I like unconventional spaces because they go well with my work, which is also unconventional. Currently, my archive is not only built on official sources, but I often go to flea markets to find material. I’m very interested in stepping out of officialdom a bit, this somewhat anarchic move that represents a bit of my freedom. Often museums have to impose compromises, outside, on the other hand, you can find the space to do everything: like once I did a 5-meter-high mosaic of this gentleman from Ethiopia with a cactus on the side. It was really impactful and impossible to do in a space normally used for art exhibitions.

E.S.: Tell me about your latest group exhibition at ArtNoble: Stratificazioni.

D:J.: The work I brought to ArtNoble gallery is a kind of image on fabric, lately I have been working with a lot on fabric, which represents a document, a passport, an identity card in which I bring together stamps, photographs, to tell other stories. I got out of the conventional medium of paper used for documents, just to change the perspective and tell the story in a different way. For example, to send postcards there was a need for a revenue stamp. I am creating this kind of document that allows for mailing by subverting the perspective, creating a postcard made of fabric as if thinking it can be mailed. The stamps that say “visit italy” inherently have almost a double meaning: as if it were a contradictory game where the real meaning is “don’t visit italy”: there is a kind of underlying tension and restlessness in these postcards that I create.

E.S.: What are you working on? What plans do you have for the future?

D:J.: At first it seemed that this atypical work I was doing was not working, for the next projects I wanted to change my mind, to go and photograph an area like a photojournalist. I then retraced my steps; I am interested in this archival work I am doing. In the future there will be a solo exhibition in Angola next month, where everything will be new. I have always worked on recovering archival material taken in markets in Portugal, on the way to Angola. I will also have a solo exhibition in Portugal in September. I am also participating in a group show at the Tate Modern next month.